Majesty & Magsterium – the 1530’s

Whether it was a collective loss of nerve or whether it was conviction – the submission of the Convocation of the Clergy of Canterbury in February 1531 was the turning point, indeed arguably, even if that argument is unfashionable, it was the point of no return. It marked a clear end if not unambiguously a new beginning.

Still in 1530 the church in England was composed of two convocations which represented the clergy in the two metropolitan Sees – Canterbury and York. The two were to all intents and purposes independent of each other; both represented the episcopate and parochial clergy; both convocations also included mitred abbots, priors and other senior representatives of the regular clergy who belonged to a hierarchy parallel to the secular clergy. The latter group were directly responsible in all matters of discipline and ministry to their local bishop and to the local church courts. They lived with and under the competing jurisdictions of civil and canon law. The regular clergy – that is those in religious orders – monks, friars, priors, canons regular, lay brothers, nuns and such – were disciplined by their order’s rule; they were responsible to the orders’ hierarchies of superiors and to the orders’ fathers-general usually resident in Rome; the code of canon law which governed them was also distinct; but ultimately – and this is vitally important – all the regular clergy were subject directly to the pope who acted in loco parentis as their bishop.

The division between secular and regular clergy was more than a organisational nicety dressed-up in a habit. The two arms of the church performed distinct functions in the medieval church. The secular clergy served the laity and brought to them the sacraments which were the seal of grace, bestowed by Christ on the faithful and which only the clergy could bestow upon the laity. The regular clergy served God though prayer. In particular they prayed the hours, the daily prayer of the church that was by the ninth century set out in the breviary; they prayed, on their own behalf, on behalf of the entire body of the faithful, living and dead. Their singular devotion to the grace of perpetual prayer enabled others of the faithful to enter heaven. To borrow a contemporary analogy the regular clergy acted like a bank of prayer upon which the entire body of faithful could draw and whose grace might be used to mortgage any soul, indeed all souls, from the penalty of sin. Central to that life of prayer, over and above the church hours, was the church’s ultimate prayer – the Mass. And it was to that latter ultimate good work that another group of medieval clerks were wholly devoted. From the late fourteenth century, particularly in England, chantries, largely founded by laymen, were endowed to secure a priest to say the efficacious prayer of the Mass for the soul of the dead departed and for his or her intentions.

Immediately it is possible to see that this structure is dependent upon a particular view of grace and salvation. And that division of clerical labour had, time and again, over fourteen hundred years, caused controversy within the church, both organisationally and doctrinally. Within the early church, under persecution, such tensions and their resulting disputes on doctrine tended to be muted but, with Constantine – after 320ce – the heresies, first of Arius and later Nestorius – both about God’s Nature – very publically and very divisively followed a fault-line that may be certainly traced back to St Paul and to the Pauline and non-Pauline traditions with their different emphases about, faith, good works and the nature of Christ and His redemption of man; and which are also more than hinted at in the Acts of the Apostles.

As the Roman world crumbled to dust; its civil order no more than a memory; its culture no more than ruins, the monastic orders from the fifth century gradually become a repository for all surviving classical knowledge. Separated from political chaos by their physical distance from urban settlement; separated from the temptations of power by the restraint imposed by each community’s observance of a collective rule, the monasteries became pioneering model Christian communities – medieval kibbutz if you will. Success bred more success as the monasteries spread across Europe – particularly into the under-populated inhospitable regions of the continent. But success also brought inevitable decline and the dominance of monastic clergy was challenged in the thirteenth century when the friars, mendicant and enclosed, with renewed emphasis on poverty and preaching, revolutionised the role of the regular clergy and in the process almost over-turned the entire structure of the wider church. In the late fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries another of these periodic spiritual upheavals, or awakenings or reformations was already underway – this time sponsored by Humanist scholars in the Universities and once again by new orders of regular clergy – leading amongst them the reformed Augustinians, reformed Carthusians, the Observant Friars all of whom had houses in London by the time of the submission of the clergy.

These regular clergy, each house entirely independent, almost a diocese to itself, posed a particular problem of management and control. They were outside the neat top down hierarchical pyramid that kept diocesan secular clergy in check. In 1530 more than half the clerical estate belonged to regular orders; more than half the church’s landed wealth belonged to these houses of regular clergy; more than half England’s clergy were effectively outside the discipline of local bishops. Even the cathedral chapters were effectively quasi-monastic as there was a usually a monastery attached to the cathedral.

Cardinal Wolsey had brought together all these over-lapping, often conflicting, always competing jurisdictions under the single umbrella of his omnicompetent legateship. It also swept-up other jurisdictions like Ireland and the isle of Man into the capacious legate’s brief. The cardinal also created a bureaucracy to manage his legateship. Wolsey had sparingly used the powers in his legatine brief over monasteries, abbacies and dioceses but its threat and his power to visit, to reform or to dissolve was the perfect weapon. He used it to overawe the church.

Fear of visitation; fear of jurisdictional encroachments kept the secular clergy and episcopate supine. By virtue of being the pope in England Wolsey also kept the regular clergy cowed. Cromwell’s genius was to see that a secular Supremacy would merely be a further adaption of Wolsey’s legatine model. It was an inspired imitation. And the dissolutions too, when they came, merely reprised on a grander scale Wolsey’s smaller scale monastic dissolutions – which had been designed to free-up resources for another purpose nearer to the cardinal’s heart – namely founding an Oxford college of his very own. Wolsey planned to be to Oxford what Margaret Beaufort, Henry VII’s mother and therefore the mother of the Tudor dynasty, had been to Cambridge. Instead the foundations of Cardinal College were barely laid before a disgraced Thomas, Cardinal Wolsey would be laid to rest in the nave of Leicester Abbey.

In 1531, using the wedge of Wolsey’s admission that the exercise of the this legatine jurisdiction had been de jure an act of Praemunire, Cromwell indicted the entire clerical estate in King’s Bench upon the king’s behalf. The clergy imagined this be a means to some larger financial end and they duly offered the king a gift of £40,000. But Henry imagined their guilt worthy of at least a king’s ransom and demanded £100,000 from the church – which the clergy offered in gratitude for the king’s sustained defence of the church from heresy but which the Henry VIII chose to accept as formal acknowledgement of their collective guilt and his due as ‘Protector and Supreme Head of the English church and clergy’.

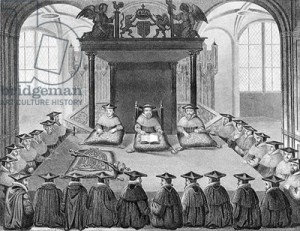

The king insisted upon this formulation being entered into the records of the Convocation. Horrified, the bishops attempted to resist the demand that they acknowledge this title as the price for royal clemency. The king refused to budge. Bishop John Fisher added what fig-leaf he could with the words ‘in quantum per Christi legem licit’ a formulation, which after debate and much froing and toing, Archbishop Wareham put to a silent convocation. The clerk to convocation hearing nothing prodded the bishops ‘qui tacet consentire videtur’ – a legal saying borrowed from the decretals of Canon Law (Pope Boniface VIII. Decretals. Bk. V. 12. 43.). An anonymous voice spoke ‘ then are we silent all’. A pregnant silence begat the Supremacy. Canterbury broken six weeks later York followed suit with only Cuthbert Tunstal, the palatine bishop of Durham, dissenting.

From that point, led by Thomas Cromwell, step by step, the clergy acquiesced to the divorce; to the king’s the new marriage to Anne Boleyn; to an new succession; to making Treason what had previously been dissent; to the transfer of papal powers, ecclesiastical jurisdiction and the Magisterium (teaching authority) of the Church – from the episcopacy in communion with the Pope – solely to the king. It was an abnegation of authority so complete that the phrase translatio imperii coined by historians to convey its completeness hardly seems to do it justice. There were only five acts of Parliament but it was all it took to end the millennium of synodical independence enjoyed by the two convocations that had comprised the English church. Each fresh Act of Parliament brought further financial penalty; each surrender to the king made the church and her bishops more powerless to resist the next.

As we have seen from the submission of the clergy, what Cromwell borrowed he greatly improved. Henry made Cromwell his vicegerent-in-spirituals and vicar general to the convocations. Cromwell was the king’s lord-lieutenant to the church. Cromwell was a secular legatus a latere from the secular pope, King Henry VIII. Cromwell would use the cardinal’s methods to manage the regular clergy: direct intimidation. Using the threat of visitation and dissolution against individual houses he was sure he could, like Wolsey, keep all in check. Meanwhile, Henry, having shaken golden apples so easily the Ecclesia Anglicana, was not slow to appreciate that the church’s orchards might yet with some careful cultivation, be made yet more fruitful. To that end, with beady calculation, Henry let his vicar general set about pruning the church’s vast financial interests.

In 1534 all the bishops surrendered up to King Henry VIII their Episcopal office granted under papal bulls; they received them back by royal grant under the Great Seal. It was the most telling of the series of ritual humiliations heaped upon the episcopate; in many ways though seeming hardly to mean anything it in fact meant everything. But even so, the piecemeal nature of the process – intentional or not – blunted clerical fears. It was not clear that the objective of the king and Cromwell was to change the nature of the church. Modern historians impute too much foresight to Cromwell which is itself too much informed by hindsight. Though it is often asserted that Cromwell knew where he was taking matters it is rather more believable that he and the king improvised from what they knew as they went along.

Yet accompanying the piecemeal alterations to the legal status of the clergy there were accompanying measures – once again piecemeal – once again they proved to be, rather like the traditionalist bishops themselves, straws in the wind. Obviously the new order necessarily needed to include an alteration to the Forbidden Degrees, which would, henceforth, include marriage to dead brother’s wife – as Leviticus and Henry ruled; but the Levitical prohibition was itself elevated to equate with those other laws of the Old Testament – the Decalogue. And buggery, a misdemeanour under canon law but a particular royal abhorrence, was made a capital offence – treason; there was a purge of the calendar of saints days; under royal injunctions images were destroyed; bishops were ordered to visit of every parish. But what cooked and sauced the secular clergy’s and laity’s goose left the regular clergy gander still at large and largely these men were most vocally resistant to the Supremacy – as the Carthusians, monks and hermits, at Charterhouse in London perhaps most spectacularly demonstrated.

In 1535 Cromwell was commissioned as Vicar General to stock-take the property of the church. The resulting Valor Ecclesiasticus was to the English church what the Doomsday Book was to Anglo- Saxon nobility. Thus, having laid their hands to the details of the church’s wealth and spooked by the resistance of the regular clergy Cromwell suggested to the king another series of monastic dissolutions. By eliminating the smaller houses it would be possible to bend the greater houses to the Supremacy. And rather as with the submission of the clergy in 1531, once more, there was a financial profit from the dissolutions that would fall to directly to the crown. The smaller houses would easily bring in another £100,000 to the royal coffers and there was an additional bonus to be gained from imposing the payment of first fruits and tenths – previously as exaction upon the bishops and secular clergy – upon the regular clergy as well. And as before behind the curtain of financial penalties hung the ultimate threats of dissolution and execution for treason. And from early in 1535 a string of executions made the latter threat into a brutal reality.

Simultaneously with this attack upon the institutional church Cromwell licensed Archbishop Cranmer – and others – to tackle clerical abuses; superstitious practices and image worship through a programme of direct reform. But their role as secular licensees served only to undermine the authority of the church; the role of the episcopate; and their joint claim exclusively to hold and exercise powers of saving grace. Traditionally this authority was made practically manifest in the ministry of the seven sacraments: baptism; confession; Holy Communion; confirmation; matrimony; Holy Orders and extreme unction. These seven ritual actions believed to be instituted by Christ and the Apostles, were necessary to salvation. And it is no small irony that it was in their defence that Henry VIII, aided and abetted by More, Fisher and others, composed another famous treatise – Assertio Septem Sacramentorum – for which the king was personally awarded by the pope the grand title – fidei defensor. After 1534 it appeared at least in the letter of statute law that this power to dispense these sacred acts grace no longer rested with the anointed ministers of the church but rather were instead located within the singular person of the Lord’s other anointed, the king.

It is has long been a shorthand employed by historians that the Henrician church remained catholic in spirit and practice. That is an illusion. Whatever the Ecclesia Anglicana became after 1534 it was not merely in schism. Schism is a division that rests on a dispute of about a doctrine within the one church – this new church where grace and truth were embodied in the king alone was not recognisably part of that one holy, catholic and apostolic church of the Council of Nicaea, Ephesus and Chalcedon. Historians in missing the largeness of Henry VIII’s claims make it possible also to miss the significance of the events in England for the wider church.

But at the time the point was not lost in Rome as Cardinal Pole clearly and repeatedly articulates from the middle of the 1530s. And it was to that same issue that Stephen Gardiner’s De Vere Obedentia was acutely and accurately directed. And for much of the next five years the traditionalists were most absorbed by debates about the meaning of the Supremacy in terms of the wider jurisdictional claims of the church. That, however, left the wider field of doctrine undefended from an explosion of heterodoxies deliberately cultivated by the nod from Cromwell and the wink from Cranmer. And indeed the traditionalist group itself was not immune from what after the last session of Trent would be considered heterodox or heretical opinion. the Bishop’s Book for example is rich in all manner of interesting if ultimately unorthodox teaching and opinion. This should not surprise historians. For the traditionalists were composed mainly of Erasmian reformers who were all seeking to explain older truths in the new language of Humanism and the light shed by textual analysis of Greek and other earlier texts on sacred Scripture.

Those at the nexus of the new religious policy, Thomas Cromwell and Thomas Cranmer, had both been sympathisers for the better part of a decade with Lutheran ideas. Cranmer’s history as a theologian at Cambridge was denoted by his associations with these reformers. A linguistic scholar of considerable gifts Cranmer had embraced the notion that philological exegesis of the books of the Old and New testament – the scriptures – would reveal the precise meaning of God’s Word. Here we need to remember that the term ‘Word’ is used in St John’s Gospel to signify the second person of the Trinity – the Word made flesh, namely, Jesus Christ Himself. Cranmer believed this scheme of literary analysis to be in every respect superior to the traditional methods of rhetorical argument based on Aristotelian models and derived from Aquinas and which we know by the shorthand of Scholasticism.

Cranmer’s considerable skills opened his eyes and illuminated his faith; his new understanding led him not only to reject abuses like indulgences and their sale but also to reject them on the grounds that they were without any scriptural authority. This liberating belief in the primacy of scripture also led him on to embrace another tenet of Luther, which the German reformer and Cranmer believed to be the only possible meaning of the actual words used by St Paul in his epistles to the Corinthians – the notion of justification by faith alone. And if by faith alone mankind is justified and saved, then all good works, including prayer, are by themselves without merit. They are not the means to salvation. Such a belief straightforwardly undermined one half of the clerical caste – the regular clergy – but it also fundamentally called into question the merits of good works or prayer and the means by which man might be saved by that ultimate of good works – the Mass.

Cranmer was not alone in taking-up these ideas, for many others, dismayed at the empty ritualism and the laxity of the entire clerical estate, also chose to take up Luther’s cause (as they had taken-up the cause of Erasmus, Colet and any number of other reformers) even if they were not always clear, at any single stage, as to what was orthodox and what heterodox. By 1530 Cranmer had also followed Luther in one other particular – he abandoned his vow of celibacy and married. As it happened Cranmer also married an ex-nun – a fact which he hid from eyes not wishing to see too much. Cranmer continued in Holy Orders and accepted his nomination to the archbishopric of Canterbury in 1532. His breaking with inconvenient vows – be it principled or unprincipled – was destined to haunt him to his end in Oxford.

The reformers assertion of the primacy of scripture chimed harmoniously with the king’s assertion of the primacy of the laws – or at least one particular law – of Leviticus. And that harmony became more and more evident as it became more and more apparent that Henry VIII could not achieve the desired annulment from Katherine of Aragon on the high ground of Levitical prohibition; a ground to which a defiant king had nailed his colours; and, from which, Henry claimed, no pope, no bishop and no man, had the power to dispense.

By comparison, Thomas Cromwell’s early religious persuasions are more opaque. His origins in the household of the great Cardinal Wolsey would not have made him more a likely Lutheran than any other man in the cardinal’s employ but like Gardiner, Stokesley, Latimer, Clerk, Tunstal, Thirlby, Vesey and any number of others under the broad patronage of Wolsey, Cromwell’s education, his humanist sympathies and his intellectual background would have made him naturally sympathetic to the wider cause of ecclesiastical reform. But whether by conviction; or by convenience; or by of a happy conjunction of the two, he was soon more; and soon he was a known patron of proto-Lutherans. From 1533, once he obtained the confidence of the king, as vicegerent-in-spirituals Cromwell took every opportunity to exploit his position to push forward Lutherans and other reformers and he also championed their radical ideas.

But it is dangerous for historians to be too deterministic about an individual’s beliefs. Oftentimes views ebb and flow; often opinions are driven as much by circumstance as by faith ; and often views change back and forth on tides of emotion as much as on rational thought. Faith is a complex matter and there is no reason for historians to think it less than complex for all the protagonists in this epic story. After all they were the ones on deck as the ship of state sailed into the storm and none of them could have known where it might end or indeed if it might find a safe harbour.

Thomas Cromwell’s practical sense of belief was also doubtless practically informed by his experience. He had sat square at the centre of Wolsey’s household and the cardinal’s world, with its tentacles spread wide through many sprawling interests. From accounting for the multiple revenues; managing the expenditures; identifying resources; acquiring them and channelling to new projects; to overseeing the vast correspondence, local, national and international; and on to exercising the cardinal’s considerable and overlapping patronage as archbishop; legate and lord chancellor; from placing men, to keeping men in their place, Cromwell had been well placed throughout and he had made the most of his position. Standing by the cardinal’s side; always ready to act; Cromwell was virtually legate to the legatus a latere apolostolicae sedes. It was a role he could therefore reprise for the king.

Capable and curious in equal measure Cromwell had watched Wolsey’s matchless genius for organisation; the appetite for detail; the skill to dispatch practical business; his ability to see the nub of a problem; his cunning in charming his enemies; his vigilance in guarding his interests; his ruthlessness in clearing obstacles from his path; his dispatch in crushing opposition; his inventiveness in turning situations to advantage; his intellectual capacity to comprehend the world; and his ambition to rule over it – if always on behalf of his master the king.

As we have seen what Cromwell saw he copied. What he copied he improved by dint of ruthless, singular, application. Cromwell lacked the bigness of the cardinal. He lacked Wolsey’s genius; he lacked his geniality; he lacked the effortless grasp; he lacked the diplomatic fluency; he simply lacked the cardinal’s vision. But an appetite for work that matched the cardinal’s; self discipline and an unrelenting determination to follow matters through which far exceeded Wolsey’s; an administrative flair that itself verged on another sort of genius; the craft of a seasoned schemer; the sinuous skill of a plotter; and ambition, a noble ambition to serve and a bottomless ambition to be noble. These were qualities which carried him all the way – to the top – and then further on – to the block.

Much has also been made of Anne Boleyn’s patronage of the reformers. It’s true that there were plenty of them in her long and expensive train. But it must be remembered that the reformers naturally took Henry’s and Anne’s side in the struggle over the divorce. That alone would have earned any able man a place in the crowded confines of Henry’s court from the late 1520’s. But Boleyn though she was she was also part of the greater Howard connection and her uncle, the duke of Norfolk, whilst hugely happy to profit from her elevation as queen was also resentful of the replacement within the king’s counsels of one upstart from Ipswich with another from Putney. Though first and foremost the king’s man, the duke was as much a religious as a political conservative. Within the queen’s courtly retinue, therefore, complex contraries of patronage were represented. In part that was to account for ease of her destruction when time came in 1536.

And it was the unexpected coincidence of domestic events of 1536 – the coming together of various elements to make the perfect storm – which really determined matters. Henry VIII and Cromwell, both, and independently of one another, improvised policy from the cataclysm. The death of Katherine of Aragon; Anne Boleyn’s miscarriage; her disgrace; the downfall of her faction; the religious tumult we know as the Pilgrimage of Grace; the king’s remarriage to Jane Seymour and her pregnancy: these events together determined the direction of the Henrician reformation in ways no amount of preparation by Thomas Cranmer and plotting by Thomas Cromwell could have achieved.

And that fact speaks to the truth of where power now lay within the church in England. And it was to that reality to which Gardiner’s treatise de Vere Obedentia most aptly found itself singularly addressed. And in time it was Gardiner’s argument rather than Cromwell’s political improvisations which proved to be the more telling. The Act of Six Articles and ultimately Cromwell’s destruction were events wrought from the iron of Gardiner’s doctrine of the Supremacy. It was ultimately so powerful a doctrine that Cranmer not only embraced it but eventually took to a conclusion even beyond the point of its own logic.

Pingback: Part II: The Royal Supremacy in the 1530′s | John Murphy