The Good Duke; a bad duke & ugly ambition….

1. The Good Duke….

1. The Good Duke….

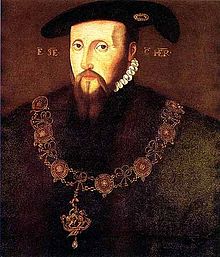

For the better part of four hundred and fifty years historians have puzzled over the career of Edward Seymour, Duke of Somerset and Lord Protector of England. Few men have risen to such heights. Few men without being a king have enjoyed such power. Fewer yet have sustained it for such a brief period.

Somerset’s emergence in January 1547 seemed predictable, almost inevitable; after his astounding victory at Pinkie in September 1547 his ascendancy appeared complete, almost unassailable. By December 1547 Protector Somerset, his brother Thomas and the Seymour dynasty over-ruled England. The Protector’s word was virtually law: he controlled the court; he controlled the council; he controlled the king. He was able to pursue any political objective he chose and the one he chose to pursue was radical. It was characterised as a reforming agenda; one that included, but was not limited to, iconoclastic religious innovation and social and economic reform.

Within two years it was all over.

In October 1549, his younger brother Thomas Seymour already an executed traitor, Somerset was ousted in a coup. Two years more he too was executed on Tower Hill. Through these events Somerset’s royal nephew of Edward VI played the role of a silent partner; or perhaps more accurately, like the silent witness whose knowing silence disapproves. Edward VI coolly watched the rise, fall and execution of both his maternal Seymour uncles without passing comment whilst passively participating in their destruction.

The Somerset regime was swept away as if a sandcastle caught on the turning tide. Although its inter-locking complex of patronage had looked impregnable it had proved more friable than fret-work; more fragile than filigree: Somerset’s regime was a febrile lattice of hot ambition and melting loyalties. How was it that a man with apparently greater power than Cardinal Wolsey; a minister without any ‘great matter’ to thwart him or without any king to restrain him; how was it that he could be so easily brought down? That is indeed the question and once it is answered fully it will explain not only the narrow events of 1547-1549 but also the entire political progress of the two decades between the death of Henry VIII in January 1547 and the arrival of Mary Stewart in England in May 1568 after her defeat at Langside.

Henry VIII’s ‘will’ had created a ‘regency council’. It was a constitutional novelty. An Act of Parliament in 1544 had provided for Henry VIII to determine the English succession and depose organisational matters relating thereto by his signed Will & Testament. And in late January 1547 on Henry’s death the regency council established under his will was, at least initially, the only legitimate conduit for the exercise of royal power. What Henry’s will determined whilst he was alive was one thing but once he was dead it was another matter; indeed it was of no matter. History teaches that the words of dead king are never more than dead letters.

In the days after Henry’s passing, whilst his death was still secret, much was settled to the naked advantage of the surviving interested parties. His principal beneficiaries did not feel themselves bound by either the letter or the spirit of their late master’s will but its very existence usefully camouflaged their own self-promotion. In effect Edward Seymour and his well prepared colleagues executed what might best be thought of as a coup-d’état. And during this succession crisis the fact that Seymour had Sir Anthony Denny on-side proved a decisive advantage. Denny was the principal gentleman of Henry’s privy chamber and the holder of the king’s dry stamp – the instrument used to execute Henry’s will. That powerful instrument enabled Somerset to buy support for his cause using the dead king’s signature to underwrite his purchase.

Edward Seymour was the eldest brother of Henry’s third wife, Jane Seymour, and consequently, maternal uncle to Edward VI. Shortly after Henry VIII’s death in January 1547 Seymour was formally promoted thrice: as Lord Protector; as Governor of the King’s Person; and as, Duke of Somerset. All three titles and dignities owned totemic political significance. The former two titles were familiar to the Tudor political class as they both had been employed during the last two royal minorities – those of Henry VI and of Edward V.

The title and office of Lord Protector bestowed upon its holder precedence in the council and in parliament. It was therefore as an office akin to regent.

A regency was exercised normally by direct blood-line relatives of a minor: a parent or sometimes step-parent; an older sibling; or paternal uncle; or another close (paternal) male relative. Queens consort also traditionally stood-in as regents to absent (or sick) husbands. In January 1547 there were two striking candidates for regency – the young King Edward VI’s eldest sister, Mary Tudor; and Henry’s last wife Queen Catherine (Parr). Although both were women they represented interests greater than their personal followings. But strong male candidates has their own appeal in the Tudor patriarchy. And so although both these women would need to be squared to clear the path, prejudices favoured male government and that made Edward Seymour’s emergence most likely and similarly made it most likely it would be via the office of lord protector. The other restricting factor upon Seymour’s inauguration as lord protector was a direct consequence of Henry VIII’s will. Though Edward Seymour’s name was first in the list of ‘regency councillors’ the council of regency was deliberately designed to limit individual power by means of collective authority. In effect the council, exercising the royal prerogative, bestowed these offices upon Seymour. This reality imposed limitations on Somerset’s executive authority.

The second office, the Governorship of the King’s Person, was of equal importance. It bestowed custody of the monarch’s person on its holder and therefore the governor of the king’s person exercised all the patronage of and access to the royal household and the wider court. In the tumult after Henry’s death it was to this office John Dudley, Earl of Warwick, encouraged the king’s other uncle, Thomas Seymour, to lay claim. Thomas Seymour’s head had long been inflated as much by easy promotions and as by heedless ambitions. Spurred-on by his over-developed sense of personal rivalry with his elder brother, Thomas Seymour needed little encouragement. He duly demanded his portion of the spoils.

Interestingly, Edward Seymour who might have been expected to know his brother better than most was clearly caught off-guard by Thomas’s demands. That error of judgment revealed Somerset’s ultimate weakness: whilst too sure of his own abilities, he was not too shrewd of others’ motives. The sibling rivalry played out behind closed doors in cold of January 1547. In short time it was to play out in wider and ever wider fora until it was so scandalously public it could no longer be overlooked by the Tudor political class.

The precedent for the division of these offices – lord protector and governor of the king’s person – between two men lay in the practice of the reign of Henry VI. This practice later was seen to sew repeated division and to have fostered factional rivalry, the ebb and flow of which were popularly memorialised as the Wars of the Roses, political events which themselves had left a visceral scar on the folk memory of the Tudor governing class.

However, the alternative precedent from Edward V’s reign, uniting the two offices in the person of a single office-holder, was hardly more promising. In 1483 the office holder in question had been the dead King Edward IV’s brother, Richard, Duke of Gloucester, who once in place quickly displaced his legal charges and seized the throne in his own right. He is known to History as Richard III and his history was the subject of partial, vitriolic but effective Tudor propaganda.

From this it can readily be seen the offices of lord protector and king’s governor did not enjoy the happiest of political pedigrees. This explains why the minority of Edward VI was met with such trepidation on all sides of the political and religious divide. It also explains the lengths to which the dying Henry VIII went in order to ensure a stable structure of collective government through the untried mechanism of a ‘regency council’, a council of equals, with Edward Seymour as no more than primus-inter-pares.

The title duke of Somerset also had its own significance and pedigree. Somerset was a royal duchy: the title had belonged to the (initially illegitimate) Beaufort children of John of Gaunt. The Beaufort brothers dominated much of the early years of Henry VI’s reign. And most significantly the daughter of John Beaufort, the first duke of Somerset, Margaret Beaufort, had married Owen Tudor; and via her by now papally legitimised ancestry, her son, Henry VII, had laid his claim to the crown in 1485. The title of duke of Somerset had briefly been bestowed upon Henry VII’s youngest son Edmund at his baptism in 1499; and finally and most significantly it again had been bestowed by Henry VIII on his own bastard son Henry Fitzroy when he created him Duke of Richmond & Somerset in 1525.

Therefore, Edward Seymour’s elevation to this title practically bestowed royal dignity on the Seymour family and with the old duke of Norfolk in the Tower and the Howard patrimony in the hands of the crown, Seymour primacy was unchallenged. Nor had this primacy come deus ex machina: no, rather, it came in the context of a long political slog between two broad factional affinities at the court; a struggle which had itself only just reached its bloody climax. In December 1546 the sudden arrest, trial and execution of Henry Howard, Earl of Surrey, heir to the old duke of Norfolk, for treason was quickly followed by the arrest, trial and condemnation of Norfolk himself also for treason; and finally as the king fought for his life King Henry excluded Norfolk’s closest ally – and the most able by far of all the leading figures of the late Henrician court – Stephen Gardiner, the bishop of Winchester – from the council of regency.

Edward Seymour is also known to history as the Good Duke. This soubriquet refers to his association, through a of a tight- knit group of evangelical clerics and their secular patrons amongst whose number we can count, Richard Cox, John Cheke, William Cecil, Thomas Smith, Michael Stanhope, Peter Carew and William Thomas who were themselves patrons of a group of religious and social radicals. These radicals included in their number a series of continental divines like Peter Martyr and Martin Bucer and firebrand intellectual gentry like Sir John Hales but also most interestingly, Hugh Latimer, sometime bishop, who espoused both radical religious and a quasi-radical social and economic doctrine. Latimer epitomised the beliefs of this group collectively identified as the ‘commonwealth men’.

The traditional history has had it that these high-minded idealists seized government with Edward Seymour in 1547 and, with the best of intentions and highest of motives, they set about completing both the Henrician Reformation whilst restoring the kingdom’s solidarity through a series of social reforms. Their great endeavour was ended in the failures of the rebellions in 1549 but their blue-print was re-adapted by the Elizabethan regime in 1558-9 and went on to its final and ultimate triumph in the long reign of last Tudor queen. This happy fiction is still widely retailed. Even the shallowest acquaintance with the Seymour clan reveals its superficial nature. The Seymour were never more than self-interested, old fashioned, dynasts. They were never political idealists.

The Seymour family had played an increasingly large part in the business of government since 1536. The family had first been propelled into the court through the its support of the Tudor dynasty in the 1490s. On the back of his father’s knighthood on Blackheath in 1497, young Edward Seymour had made his way to court and up through the lower rungs of the chamber and privy chamber. His closeness to the king enabled him to gain preferment; land and, ultimately, places for both his sisters Jane and Elizabeth as ladies in Anne Boleyn’s household once Anne had displaced Queen Catherine at court in 1529.

After the divorce and Anne’s coronation the Seymour girls were even better placed. As matters turned-out they were too well placed for Boleyn fortunes. Edward’s elder sister Jane caught the king’s eye just as his passionate irrational love was turning into an equally passionate irrational hatred of his second wife. As Anne’s rise had elevated the Boleyn, Jane Seymour’s rise on the swell of royal favour swept up Edward Seymour and her entire family. Hers was to be the marriage which produced the longed for male heir. And on the basis of that success good fortune smiled continuously on the Seymour for the remainder of Henry VIII’s reign.

By 1537 Jane was queen; her sister Elizabeth was married to Thomas Cromwell’s son; Edward was created Earl of Hertford and her younger brother, Thomas, was soon prominent at court serving in royal embassies to Francis I and Charles V. Somewhat flamboyant, somewhat handsome, and equally as ambitious as his elder brother, affable Thomas soon cut a figure of his own in the court; duly winning his political spurs in the wars of the 1540s. In those same military adventures Edward Seymour cemented his own more sober military reputation. Edward Seymour’s rising star as a general was seen to be eclipsing that of the duke of Norfolk. The duke had looked to his talented eldest son who was the equal in every respect of Thomas Seymour: an accomplished soldier, a flashy courtier and a gifted poet. But Henry Howard, Earl of Surrey was also grandly superior in one vital respect – his lineage. Not only was he the scion of the Howard dynasty he also had royal blood, Plantagenet royal blood , coursing through his veins. Surrey answered Seymour pretensions by quartering his mother’s Plantagenet arms on his own. His new coat arms was executed with a public flourish which Henry VIII as publically put down with the executioner’s axe.

Bitter factional rivalry in the Tudor court had flared up periodically since the rise of Thomas Wolsey. In the mid 1540s it had resumed once more as this restless younger generation were making their way in the shadowy winter days of Henry’s closing years. Rivalries burned at least as intensely as before. As the Howard had sought repeatedly to build their affinity into the house of Tudor, by means of marriage, to make permanent the caprice of favour; so, the Seymour struggled to displace the Howard ascendancy, in order to make secure their own position.

Conveniently, for historians, like the struggle between the’ two roses’ in the fifteenth century, this mid Tudor struggle became characterised by the religious sympathies of the two large loose factional groupings – the Seymour as patrons of religious reformers and social radicals; the Howard as patrons of religious traditionalists and political conservatives. But like the business of the ‘two roses’ – it was more complicated than either a factional struggle alone; or, a confessional struggle alone; or, that favourite of historians, a combination of the two. But the dynasty-building of family provided a centrifugal spin to the political whirlpool already whipped up by the progress of the tornado of the Henrician Reformation across the settled social and economic landscape of Renaissance England.

The Seymour dynasty was not without its own ambitions and vanities. Curiously they were perhaps best personified by the two Seymour wives – Anne Stanhope, Duchess of Somerset, and Queen Catherine Parr, who surreptitiously married Edward’s younger brother, Thomas Seymour, without the permission of the council in March 1547. Her marriage to the newly ennobled Lord Admiral was important for many reasons. Catherine’s position as dowager was itself already privileged. She had her own income; her own apartments at court and access to the young king in her own right. She was also already established by the council as the guardian to the king’s younger sister Elizabeth. Catherine’s houses at Chelsea and Hanworth were places of resort for an influx of continental divines. The queen was an avid reader and writer. Her compositions of prayers and such were published whilst she was queen and later in 1547 the published a second work – The Lamentations of a Sinner. Officers in her household had links to Cheke, Cox and others close to the young king. The queen dowager’s position within the royal family also brought the king’s first cousins Jane and Catherine Grey into her social orbit.

Catherine Parr was complex and ambitious. More than any of Henry's wives she was truly intellectual. She was a more cultivated than Anne Boleyn; and more socially intelligent that Henry's second wife. She was much better educated than Catherine of Aragon. She had a high opinion of her intellect and some inside the Tudor political patriarchy were inclined to see her as something of an opinionated radical.

As before, the same pattern of family promotion had followed from Catherine Parr's elevation to status of Queen consort. Her brother, William Parr and her brother-in law, Sir William Herbert, were prominent members of Henry VIII's privy chamber and named in the king's will to the council of regency in 1547. Like Henry's first wife, Catherine Parr was made regent during Henry's last military expedition to France. It gave her a taste for power and politics from which she never shook herself quite free. Early in 1546 it almost ruined her but the king was minded to overlook his wife's religious indiscretions. In January 1547 she was sufficiently indiscrete for the Imperial ambassador to know she expected to be named as regent. But despite his many wives and his obvious respect for female intellect Henry VIII's long standing prejudice against female government held firm to the end. He passed over his last wife and she in turn found herself tempted into a third marriage - this time to a man her own age - the dashing Thomas Seymour.

For Thomas Seymour the dowager queen’s social and political status added to her allure but Catherine was surely more politically ambitious for herself than history has allowed. Her secret marriage to the young king’s favoured uncle came hard upon the heels of Thomas Seymour’s unexpected emergence to be a principal amongst the leading players in the council. Her marriage was an act of defiance to the councillors who had snubbed her; and a gamble on the young king’s favour towards Thomas of which Catherine would have been aware from first-hand. Equally Thomas was as aware of Catherine’s unique position at court; her access to the young Edward VI’s and his sisters; and this marriage gave Lord Admiral status second only to that of his brother. It placed him at the heart of the Tudor dynasty. And Thomas Seymour was not slow to exploit this access in an attempt to ingratiate himself with the lady Mary; the lady Elizabeth and the lady Jane Grey. Thus Thomas’s marriage to Catherine Parr created a natural counter-weight to the accumulation of political power in the hands of the duke of Somerset.

Almost immediately upon the marriage a second rivalry paralleled that between the Seymour brothers, namely the one between the duchess of Somerset and the dowager queen. The duchess laid claim to the queen’s apartments at court; to her place in precedence as she claimed Catherine Parr was now merely Lady Seymour and no longer queen dowager. Catherine Parr refused to give up her place. In front of the court the two pushed each other aside entering and leaving the great chamber. The duchess refused to carry the queen dowager’s train. The queen dowager refused to hand over her jewels to the duchess. The two women used unkind words in public: the duchess claiming ‘if master admiral teach his wife no better manners, I am she that will’ the queen riposting that the duchess was no better than a ‘living hell’. The rivalry not only consumed the women but duly destroyed both their husbands. The stormy public spats between the wives were surrogate for a deadlier political game being played out sub rosa by the Seymour brothers.

Anne Stanhope was the daughter of the Sir Edward Stanhope (of Rampton) and Elizabeth Bourchier (sister of

John Bourchier, Earl of Bath and a descendant of King Edward III). Anne had two half-brothers from her father’s first marriage to Avelina Clifford. They were (Sir) Richard Stanhope and (Sir) Michael Stanhope. Through her mother, Anne was a direct descendant of Thomas of Woodstock, the youngest son of King Edward III of England and Philippa of Hainault. With her high noble family connection Anne came to court in 1511 as a maid of honour to Queen Catherine of Aragon. Sometime around 1529 she and Edward Seymour fell in love. She persuaded him to repudiate his first wife Anne Filliol. Edward Seymour was married to Anne sometime before March 1535. They were to have ten children. Therefore, it must reasonably be assumed it was a happy marriage. But there is equally plenty of anecdotal evidence that the duchess was as imperious, short-tempered, outspoken, bitter, demanding and quick to take offence as she was fecund.

It is hard to find another woman in the Tudor court who can so readily be matched to so much contemporaneous invective. By any measure she makes the irascible Bishop Stephen Gardiner the silver-tongued courtier. In a sense she was the Sarah Churchill of her time - and as the duchess of Marlborough later, Anne Stanhope was both the making and un-making her husband's fortune. She made it by providing the amorous Henry VIII with apartments where her married modesty provided a respectable cover for the king's trysts with Jane Seymour in 1535 and 1536. She marred it with her increasingly intemperate behaviour, to her husband; to his brother; to Thomas's wife Queen Catherine; to her step-brother Michael; to the archbishop of Canterbury; to the Imperial ambassador; and, to the entire council meeting at Somerset House - in public and in private.

The harangues of the duchess of Somerset were soon the stuff of legend. In the claustrophobic confines of the Tudor court social slights became greatly exaggerated. A child-monarch could exercise no restraint over adult misbehaviours. This natural institutional failure was magnified by the organisational methods employed by Somerset (and his wife) in managing the king's personal affairs. Business in the form of council meetings; correspondences; ambassadorial discussions; even routine administration were conducted in the ambit of Somerset House. The young king was placed under the governance of Sir Michael Stanhope, the duchess's brother, who was appointed vice-governor of the king's person. Stanhope kept his charge in a splendid isolation; short of cash; deprived of company and entertainment. Even the bookish young Edward VI chaffed under these restraints.

The king's 'good uncle', Thomas Seymour, readily supplied to the king what Stanhope and Somerset denied. Thomas Seymour secretly gave Edward VI unauthorised gifts and bribed the king's body servants in order to conduct an unfettered correspondence with the king. The vigilant and busy Stanhope, who conducted repeated raids into the royal bedchamber to check on royal excesses, missed the conspiracy budding under his nose.

Although Somerset had safely emerged the victor for the scramble for office and power by the time of Edward VI's coronation in February 1547 for much of the next nine months the council continued to exercise a check upon his ambitions. And what had been bought in the dark days of January had to be paid for, favour for favour. As Edward Seymour was named duke of Somerset; lord protector; and governor of the king’s person; Thomas Seymour was promoted to the peerage as Baron Seymour of Sudely; promoted into the privy council although he had not been named to it in the will on which the ink barely dried before it had been amended. And Thomas Seymour was also made Lord High Admiral in succession to the John Dudley who was himself now the newly promoted earl of Warwick.

The tight-knit group of fifty or so noble families were to find their number repeatedly augmented in the six years after 1547 and many knighthoods were bestowed to augment the ranks of gentry. The precedent for this inflation of honours was set in these few weeks after Edward VI’s accession.

From this point forward the tumble of new titles makes it difficult to follow the principles in this story as barons become viscounts; viscounts earls or marquises; and earls or marquises dukes. In 1547 Thomas Wriothesley is created earl of Southampton; William Parr is created Marquis of Northampton; William Paulet is created Baron St John and later Marquis of Winchester; Sir Richard Rich created Baron Rich; Sir William Willoughby created Baron Willoughby; Sir Edward Sheffield made Baron Sheffield. Others received pensions; land grants and great household offices: Sir William Paget made comptroller of the royal household, then later Lord Beaudesert; the earl of Arundel is made lord chamberlain; Sir John Freston, cofferer. Pensions and grants of land were bestowed on a scale unknown for two generations.

This tide of ennoblement ebbed only upon the young king’s death in 1553. Male profligacy honours was succeeded by female parsimony as neither Mary I nor Elizabeth I were minded to imitate the example set in their brother’s reign. and Mary made no secret of her opinion that the council’s greed set the worst example to the commons and fed popular unrest. In one interview with a group of privy councillors and divines sent to persuade to have the new service in her house she sourly observed that ‘Master’ Ridley might as well be of the council ‘as it goeth these days’.

In addition to the creating of the council of regency Henry VIII's will had made a number of ancillary provisions amongst the most important of which related to his two daughters Mary and Elizabeth. They were both left large annual pensions: in the case of Mary £3500; and, in the case of Elizabeth £2500. These considerable sums were to be paid annually. The old king was shrewd enough to see advantage is having his daughters simultaneously rich and simultaneously dependent for their income from quarter to quarter upon the new regime.

However, cash-strapped, the government was already compromised by pensions and land grants made in its own interest. It was anxious to avoid further recurring charges. Moreover, as it made preparations for an early resumption of hostilities with Scotland it needed all the ready money it could lay its hand upon. In addition Mary (and Elizabeth) were shrewd enough to understand that pensions paid in the debased specie by which the government conducted its cash business were unlikely to hold value.

Mary also was old enough and canny enough to take advantage of the simmering rivalries at the heart of the new government. Thomas Wriothesley sudden and early disgrace as lord chancellor at the end of February 1547 gave the heir presumptive an ally who proved extremely important to Mary. Mary sent Wriothesley gifts such as personally embroidered cushions. Robert Rochester, Mary's household comptroller, also had long standing connections with both Chancellor Wriothesley and Bishop Gardiner. There is no evidence of the actual negotiations that took place between Somerset, the council and Mary. But there's hard evidence of their outcome. Mary was given ownership of the larger part of the vast Howard land-holding in East Anglia. History has long had a low opinion of the Spanish Tudor, the sad, dull, catholic, Mary. In the conventional reading of English history it would be inconceivable that this extremist dullard would have been capable of such a cunning negotiation on her own behalf. The facts however stand for themselves and bear no contradiction - least of all contradiction rooted in its own blind prejudice

Immediately upon her accession to the Howard patrimony Mary became de facto one of the greatest noble magnates in England and the dominant presence in one of the most important economic regions of the kingdom. The grant of lands included both the duke's grand house at Kenninghall and the royal palace at Beaulieu (also known as New Hall) which famously was Henry VIII's first great building project. And what Mary gained she was to hold undiminished through a series of extremely challenging political circumstances, only early in 1553, to further enhance her status with the addition of Framlingham and a number of manors in the region.

By the time this initial deal with Mary had been done Somerset became aware that his brother had contracted a secret marriage. Thomas Seymour's attempted to enlist the lady Mary's assistance in supporting ex post facto his marriage to Catherine Parr, the queen dowager. Mary response was cool. Her tone carefully crafted to convey a temperate, level-headed restraint in contrast to the hasty actions of hot-headed younger Seymour brother.

'....of all the poor creatures in the world it standeth least with my honour to be a meddler in this matter considering whose wife her grace was of late....if the remembrance of the king's majesty....will not suffer her to grant your suit I am at nothing able to persuade her to forget the loss of him who is as yet very ripe in mine own remembrance....' ( Original letters, illustrative of English history; with notes and illustr. by H. Ellis, Volume 2 p.150)

It was a tactic that she would employ successfully again and again. Just as she saw she could take advantage from Thomas Seymour's marriage the late spring of 1547; so, in July 1549 she took advantage from Somerset's weakness to negotiate a private religious settlement; and later in 1551 she used the caprice of an Imperial abduction to add leverage to her dispute over the arrest of her servants and her continued use of the Mass; and finally, in February 1553 she almost certainly negotiated some settlement with her brother (which was duly over-taken by events) but left her even more powerfully entrenched in her East Anglican stronghold than before. Ironically Mary only gained the Howard castle at Framlingham in May 1553 that was within two months to provide her army headquarters in the struggle for the throne.

If Elizabeth had delivered such a string of coups de grâce her claque of popular historians would noisily applaud her skill and sagacity. But we are blind to Mary's strategic sense as we are deaf to her wise words. Yet, although Henry VIII's eldest daughter may have been short-sighted she was not myopic when it came to seeing her own advantage. And in his dealing with this manipulative twenty nine year old spinster Somerset's inexperience showed. Within two years the duke would come to be haunted by his repeated errors in managing the heir presumptive.

The first phase of the Protectorate of Somerset was consumed preparations for and then fighting a war in Scotland. The military and diplomatic work initiated by Henry in his last years had left England with unfinished business. The old king had soundly beaten the Scots in 1542 and the sudden death of his nephew James V had presented a further opportunity to consolidate his victory by means of uniting the two kingdoms by marriage. Scotland's crown had fallen to James' only surviving child - a daughter - Mary Stewart, Queen of Scots. As the price of peace the infant Scots queen was betrothed to Henry's son Edward.

However, despite the 'rough wooing' Henry had trouble drawing the weft of Scots promises through the warp of English interest. The Scots - or rather Mary Stewart's mother, Mary de Guise - refused to hand the queen of Scots over to the English lords sent to fetch her to Whitehall. The stand-off presented a challenge to the English and an opportunity to Somerset. If he could repeat Henry's victory at Solway Moss with one of his own and secure Edward's royal bride thereby uniting two crowns, Protector Somerset would be unchallenged. He could be free from the restraints of the council; he could be secure in office until the young king came of age and, perhaps, well beyond. A grateful nation and a grateful king would be permanently in Edward Seymour's debt.

Somerset quickly moved the council to make preparations for a military strike against the Scots. He intended to use overwhelming force to achieve his ends. In addition to Henry's considerable artillery train, Somerset, making certainty doubly certain, furnished a mounted cavalry of some 6000 men; several hundred German mercenary harquebusiers; and a contingent of Italian mounted harquebusiers under Don Pedro de Gamboa. This overseas aid had to be bought with precious gold but the army itself could be paid for with newly minted coin.

War, therefore, necessitated the continuance of the government’s policy of debasement of the coinage – but at an ever accelerating rate. This was probably the motivation for making Sir Edmund Peckham a member of the council. Peckham had been Henry VIII’s High Treasurer of the Mints since 1544 and from that office he had masterminded the first phases of the great debasement. By 1547 the Tower mints alone could no longer cope alone with the pace of production. Smaller local mints like those in Bristol, Durham, York and Newcastle were commissioned to call-in old and issue new coin.

The Bristol Mint had long been under the patronage the lord admiral and thus, it fell in February 1547 under the influence of Thomas Seymour. He soon turned the council’s mint official, Sir William Sharington, into his personal client. Thomas Seymour and Sharington used the Bristol mint as personal money-making machine. By 1548 no one could make out how much silver bullion had gone missing; how much coin had been minted; how much of both had been embezzled. It was enough for Thomas Seymour to brag he might raise an army of his own to hold the king. At the time his foolish talk was dismissed as the ravings of a grieving widower. But once the council started to investigate the extent of Sharington’s accounts it became apparent that the scale of their embezzlements could not be readily calculated – not even by the perpetrators.

Thus, the war in 1547-8 was financed through a series other one-off revenue raising schemes. After the manipulation of the coinage the largest of these was the dissolution of the chantries. It might alone have furnished an army but much of that hoard was earmarked for pensions and rewards for the councillors. The formal process of dissolution had to await Parliament which was put off until November 1547. Then in the aftermath of Somerset’s stunning victory over the Scots at Pinkie all the chantries were suppressed. The dissolution of over 2000 institutions impacted upon villages and towns where guild chapels and chantries had played a large role in educational provision. The chantry dissolutions and the dissolution of the guild chapels also prepared the way for a concerted attack upon the remaining elements of traditional religious doctrine.

In military affairs too much success is often as fatal as too little. Somerset’s devastating victory at Pinkie was too complete. The Protector returned to London a conquering hero leaving the English armies marauding all over the Scottish lowlands. Their objective was simple: they were to terrorise and cow the Scots until they had cornered and caught the young queen. Once finally in English hands she was to be brought to London. Once more the majority of the Scottish nobility promised to hand over their queen to the victor. But as before promises were one thing but seizing the young queen another. And the English presence gave Mary de Guise her chance to invite in the French. In return for military support the queen mother promised Henri II the one thing she could – the hand of her daughter for the dauphin. It was an irresistible bargain. The French came to the rescue and Mary Stewart was spirited from her homeland destined for Paris and the crown of France.

Somerset had appointed Sir Ralph Sadler, a protégé of the Protector’s eminence-grise Sir William Paget, as his ambassador. Somerset could hardly have chosen a man less suited to the task. Sadler made enemies out of friends. He disliked the Scots and spared none of the lairds his easy contempt. Sadler misread the politics of Scotland; he misread the sullen acquiescence of the lowlanders; and above all he misread the cunning and political craft of Mary de Guise. The march of victory turned with the season. By 1548 the English were trapped in a war of attrition for which they were essentially ill-equipped to fight. And back in London Somerset could not resist in interfering in military matters many hundred miles away. He refused additional manpower and munitions to John Dudley, the newly made earl of Warwick, who had been left as one of the army’s senior commanders in a peremptory fashion. Not only did the failure to hold Dundee let in the French it made Somerset’s superior tone made an enemy from Dudley and the military leaders like Russell and Willoughby who served with him. In 1549 that enmity proved Somerset’s un-doing. Somerset was had a way of rubbing-up his colleagues the wrong way. Sadler was the wrong person in the wrong position and as ineffectual as Somerset was interfering – the military campaign quickly deteriorated into a hostile rivalry.

As the winter of 1547 approached and the first Parliament of Edward ‘s reign assembled in Westminster. It appeared to one and all that Somerset was tantalisingly close to plucking the Stewart rose from the Scots thorn. Parliament heaped honour upon the protector as indeed did his young nephew. By proclamation Somerset was seated above the nobility, in his own place under the royal canopy in the house of Lords. The Letters Patent which had appointed him lord protector were confirmed in statute – and no longer merely for the duration of the royal minority. The court and commons bowed to him as if he was king. Somerset had reached the heady heights but the capricious Fates who had raised him high were about to cast him down.

Early in 1548 it was clear events in Scotland had turned against the English. The policy of harrying the lowlanders from various strongholds became undermined by Somerset’s decision, over-ruling his commanders on the field, to concentrate English forces in Haddington and Berwick. Then in the spring and summer relentless English propaganda about uniting the kingdoms into single political inflamed Scots pride. In June the arrival of 10,00 French troops met widespread support from the local populations weary of English predations on their lands. The French forces too concentrated their military efforts on Haddington. The demanded the infant Scots queen be sent to the dauphin. The queen mother naturally readily acceded to these requests and within weeks Mary Stewart had slipped out of the reach of the English army. The central objective of the war was lost.

The military focus switched from the capture of Mary Stewart to the English army, heavily dug in Haddington, south west of Edinburgh. The war turned in six months from a fast moving campaign of battles and skirmishes into one of attrition and siege. The weather frustrated English attempts to relive the garrison and though Haddington held success came at high price. There were heavy losses of men and materiel. The other English strongholds were a steadily abandoned. This ensured Mary de Guise gradually gained a grip on the kingdom just as it exposed the lands of the Scots lairds who had joined the English cause to their enemies. The emboldened French were able to support their Scots endeavour with feints on Boulogne and Calais. These necessarily drew resources away from Scotland. Finally, just as a domestic crisis was about to explode over Somerset he agreed to withdrawal from Haddington. Having staked so much symbolically upon so little – the withdrawal undermined confidence in Somerset’s judgement.

Meanwhile Thomas Seymour had not been idle. Having suborned the king’s groom John Fowler, the lord admiral had been dispensing cash gifts to Edward and the king by return had scribbled various note to his uncle on scraps of paper. Thomas as ever read too much into too little. He spent the early part of 1548 enticing the ambitious Grey family into his web of intrigue. Lady Jane and Lady Catherine joined the lady Elizabeth both at Chelsea and later Sudely. These family gatherings soon gathered their own notoriety. Thomas Seymour played rougher than a gentleman ought to with the royal ladies and to some extent his wife played her part. It was only when early one morning that the lord admiral was found under-dressed in Elizabeth’s bedchamber that he became undone.

By this time Catherine Parr was pregnant. The wilful and wayward young Elizabeth was sent away to Hatfield. But the gossip reached court and eventually the ears of the duchess of Somerset. Catherine Parr gave birth to a baby daughter, named Mary to honour the heir presumptive. Mary and Catherine had made their peace with one another in the backwash of the scandal over Elizabeth. But within hours the dowager queen was dead of puerperal fever.

Events now gathered pace at an alarming speed. The lord admiral was back in London for Parliament. Thomas Seymour dined with many of the council and his talk was fevered and treasonable – though no one seemed to pay him much heed. Somerset and the duchess looked coldly upon Thomas’s proposals for a new bride. Shunned by the heiress presumptive he turned his attentions instead to the more malleable Lady Elizabeth. it may well have been another attempt to stampede the council into approving this most unlikely marriage that led him to attempt to abduct the king. He burst into Whitehall and made it as far as the privy chamber where he ran through one of the king’s dogs before being arrested.

The investigation that followed upon the lord admiral’s arrest was bound in the end to lead to Thomas Seymour’s execution. But on route the investigators unearthed a trail of scandal – over the admiral’s unseemly conduct with the lady Elizabeth; the king; the mint in Bristol; the Grey family; the lack of security in the court; the mismanagement of the Sir Michael Stanhope; the distance of Somerset from his colleagues and many blamed it all on Somerset’s grand hauteur exemplified by his absence from the royal household. The revelations that condemned Thomas Seymour but they also provided a devastating indictment of Protector Somerset’s conduct of government.

Finally, and most shockingly to his peers, Somerset was forced to acquiesce to the execution of his own brother without a proper trial but instead by act of attainder. although he absented himself from the vote on 27th February 1549 Somerset’s reputation never recovered from this ignominy – it was seen in the Tudor governing class as akin to the action of a Tyrant. That Lent of 1549 Hugh Latimer went to extraordinary lengths to defend Somerset from his enemies but to no avail. Instead of one, two reputations were trashed. Latimer was never again asked to preach at court. If Latimer’s eloquent defence of the regime had persuaded any of his audience his words evidently failed to persuade the king.

Undermined from within the Seymour family, Somerset was now besieged from without. The radical commission under Hales had managed to stir-up discontent wherever it went. Inflation ignited by the debased coinage had now taken hold not only of government finances but was forcing up grain prices. At the same time the destruction of the chantries and the consequent closure of village schools loosed yet more uncertainty. Religious innovations were also unsettling order: first, in 1547 there was the destruction of images and rood screens; then later in the year promulgation of Cranmer’s homilies – full of Lutheran and Genevan theology; the introduction of an English communion service into the mass and in 1548 communion under both kinds was imposed; itinerant preachers stirred-up the commons just as the dissolutions were taking full effect. Diocesan visitations imposed the new practices on reluctant parishes. And parliament finally authorised a new single service book to replace the Mass and Latin sacramentaries. Thomas Cranmer’s Book of Common Prayer was due to be promulgated on Whitsunday 1549. The conservatives on the council pleaded with Somerset to postpone it but the Protector dismissed their suggestions out of hand.

Then came rains, storms and floods. And there were spontaneous outbreaks of rioting and reports to the council of ‘stirs’. The government was sufficiently to alert the local magistracy and gentry and to dispatch justices of the peace into the countryside. Sporadic outbursts of popular discontent were not unusual and many in the government had been involved first hand in putting down the Pilgrimage of grace in 1536 and were not squeamish about using force to crush rebellion. Edward VI’s chronicle lays out the extent of what happened next:

The people began to rise in Wiltshire, where Sir William Herbert did put them down overrun and slay them. then they rose in Sussex, Hampshire, Kent, Gloucestershire, Suffolk, Warwickshire, Essex, Hertfordshire and a piece of Leicestershire, Worcestershire and Rutlandshire where by fair persuasions…partly by gentlemen they were often appeased….and again….because certain commissions were sent down to pluck down enclosures, then…did they rise again….

…..after they rose in Oxfordshire, Devonshire, Norfolk and Yorkshire….

(W.K.Jordan, Chronicle & political papers of King Edward VI, p12-13)

On Whitsun in the tiny village Sampford Courtenay a local riot over the new prayer book took hold and flared into a serious rebellion. The Western rebellion quickly spread. The rebels had Exeter in no time and as in the pilgrimage of grace in 1536 the rebels marched under the banner of Christ’s five wounds. Once in Exeter they issued demands amongst which most prominently was the restoration of the Mass.

By now the council was alarmed by the scale and number of rebellions and they demanded Somerset put down the rebels. Somerset aided and abetted by Cranmer prevaricated and sought rather to reason with them. Just as the government was cajoling one group another rising took hold – this time in the east under the leadership of Robert Kett. The motives of the eastern rebels have always been seen as economic rather than religious as that in the west have been seen as religious discontents rather than social unrest. But the social unrest was sufficiently widespread to be characterised as more as a loss of grip upon localities by central government. This certainly is how Sir William Paget chose to characterise the situation to Ambassador Van der Delft in July 1547.

Van der Delft was in close contact with the heir presumptive. Many on the council were disillusioned with Somerset. Mary and the imperial ambassador took full advantage of the situation to secure a Mary’s exemption from the new religious dispensation – using the not so subtle threat of force. Many now saw Mary as the best hope for securing stability during the king’s minority. Mary was popular and clearly politically adroit. Led by Wriothesley, Arundel and Peckham but including more politique figures like John Dudley and John Russell many saw this was their moment to strike down the Somerset and the Seymour once and for all. The Imperial ambassador taking his cue from Paget’s careful confidences assured the Emperor Charles V that his first cousin would soon be regent of England.

Somerset, cornered, had no choice but accept the council’s clamour to assemble two armies to put down the rebellions. however, he was well aware from Paget as from other sources that if he left London and the king he was finished. Therefore he gave Dudley the command on the army which was to put down Kett and Russell the command army to put down the rebels in the West. The two generals left London in Somerset’s hands but once they had crushed the rebels they had the means in their hands to put an end to Somerset’s protectorate and to Seymour primacy. In September 1549 Somerset sought to delay the inevitable by seizing the person of the young king and dragging him in the middle of the night down-river to Windsor castle. It is no small irony that boy he had studiously ignored now became his only shield. But it was already too late. but as it turned out the real winner from this fractious upheaval was neither the council nor the conservative phalanx who wished to replace a protector with a regent – rather it was the king who seized the day and finally made his voice heard in the counsels of his realm.

Pingback: Part III: The history of Edward Seymour, Duke of somerset | John Murphy