1. Brushes With Reality

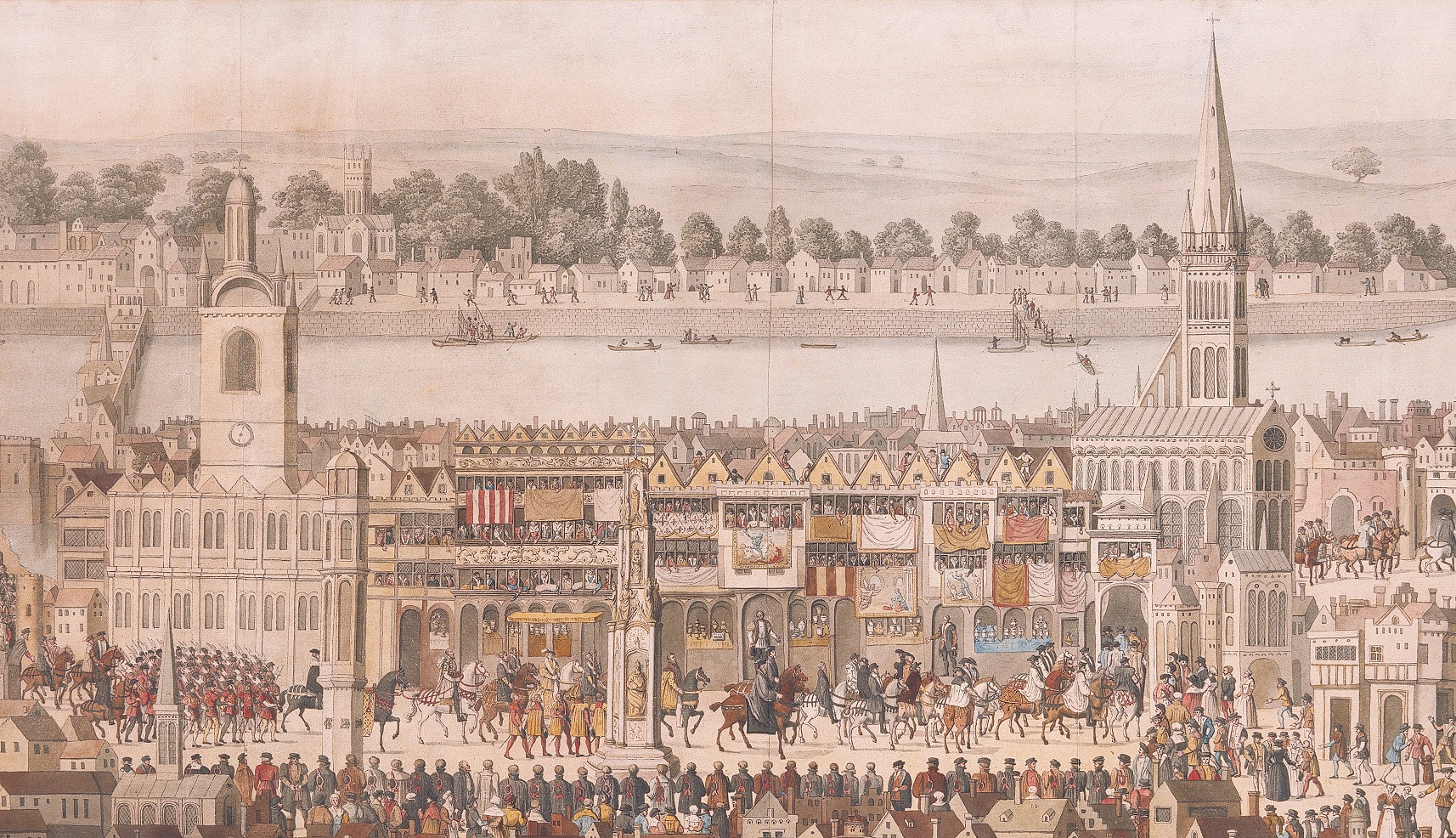

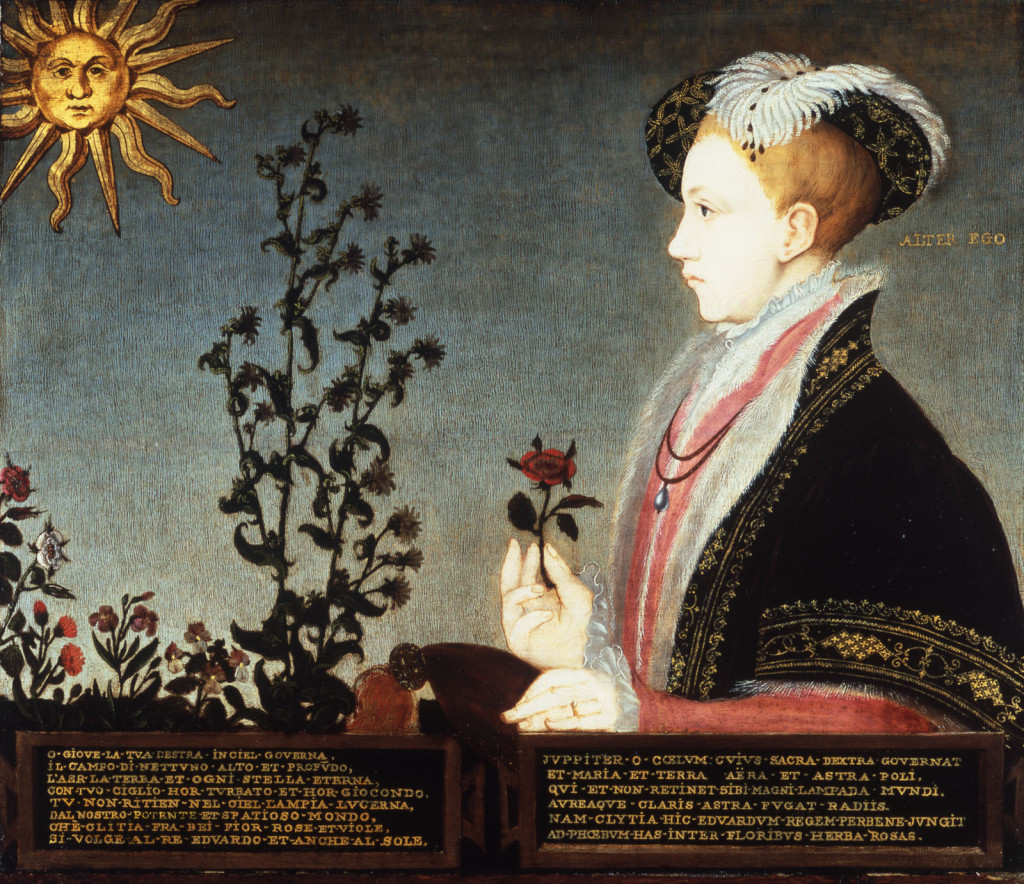

This famous “sun” portrait of Edward VI (above) currently hangs in Compton-Verney. Like his Yorkist great grandfather and namesake Edward IV, the sun was to be the motif of this Tudor King Edward. The portrait is usually dated to around 1550.

The sun portrait comes to us via the Stanhope. The Stanhope were the brightest of aristocratic stars by the time the Whig oligarchy of the eighteenth century but their sun first rose in the 1540s, in Edward VI’s brief reign. The story of that rise and fall, paints its own picture of the politics of the middle decades of the Tudor century.

The portrait of Edward VI is attributed to William Scrots. Scrots had been a court painter for the Regent’s court in the Netherlands. His portraits of leading members of the Hapsburg dynasty were regarded as groundbreaking. By the time of this sun portrait of Edward VI, Scrots’ brush had already carefully shaped his royal image – first in the famous anamorphosis of 1546 and also in another study of of the young Prince of Wales also holding a rose (see below left).

Scrots notable innovation was to present Edward VI in profile – a representation hitherto largely associated with coinage. It was a fashionable accoutrement of Mannerist portraiture to have the sitter hold a flower. Flowers owned Ovidian symbolism. Edward’s flower presents him as the apogee of the Tudor dynasty – in the “sun portrait” both the Lancastrian red rose and the Yorkist white rose look towards him whilst his gloved hand encloses the Tudor emblem, the wild sweetbriar rose.

This rose was also associated with purity and virtue: “there is no rose of such vertue as is the Rose who bore Jesu.” In Edward’s hand the sweetbriar underlines the purity and virtue of his lineage. It is all too easily forgotten that Edward’s legitimacy, alike his half-sisters Mary and Elizabeth, had been occluded by Henry VIII’s marital incontinence. The papacy had specifically declared marriage to Anne Boleyn invalid but Henry’s later excommunication rendered all his subsequent marriages extracanonical and their offspring were consequently illegitimate under Canon Law. The English rose in Edward’s hand makes its own sweet point.

Scrots had been tempted to come to England by an enormous salary of £62/10 shillings. Like Holbein before him, once in England, Scrots found patrons aplenty – all longing to be immortalised in oil. It may well have been England’s roving ambassador to the Emperor throughout the 1540s, Bishop Stephen Gardiner, who first cast the bait that landed this artistic salmon. Scrots certainly was quickly taken up by Gardiner’s friends at court and most notably Henry Howard, Earl of Surrey.

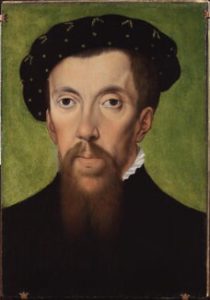

Upon arrival in England and in fairly quick succession, Scrots painted two studies of Henry Howard. Quick succession was the impatient expectation hovering over the Earl of Surrey’s ambitions. If Thomas Howard, the third duke of Norfolk and Earl Marshal, was the “Priam” of the ducal house of Howard, it was Henry, Earl of Surrey who was the dynasty’s “Hector”. Poet, soldier and courtier – dutiful husband and father – by 1546 Henry Howard had already fulfilled many of the ideals of the Renaissance “prince”. So much so that Surrey glamour is a model for Shakespeare’s depictions of a Renaissance princes.

Scrots last and most famous depiction of Henry Howard, however, lays claim to far more than that abstract ideal. And the deceptive shallows of ambitious appearance were perilously dangerous in the dying years of Great Harry’s reign. It is, therefore, noteworthy that no one in the Tudor court bar the king himself, had his portrait painted more than Henry Surrey. Scrots final portrait made that statement in a form that Surrey’s career had already made proforma.

As with the king, Surrey’s love of art was real but art was a deadly serious business in the politics in Renaissance courts. By the mid 1540s, alike the king, Surrey had built boldly and ambitiously and in fashionable high Renaissance style. His rivals at court noted his building ambitions – and Surrey House on the outskirts of Norwich, also attracted its own architectural rivalries. Surrey’s dynastic rivals for Henry’s favour, were the Seymour. Queen Jane’s elder brother, Edward Seymour was also a grand builder. His castle in the air was at the far end of the Strand and once he became Lord Protector and Duke of Somerset, after Henry VIII’s death in January 1547, Seymour’s grand project, Somerset House, consumed a fortune. It was destined to become a marble mausoleum for the Seymour and their dynastic political reputation much as the decay of Surrey House would be the epitaph for Surrey. But, In 1546 as Scrots brushed young Surrey into history, that was as yet in the future.

Henry VIII was never one to overlook the politics of art. He looked on what others built and if he saw it was good he often wanted it for himself. That sense of the importance of art and architecture in making the royal image into an imposing reality was Cardinal Wolsey’s very particular gift to Henry VIII. Hampton Court and Whitehall – York Place – were the cardinal’s follies. With Wolsey gone, Henry then built bigger than the cardinal. After enlarging and reimagining first Hampton Court and Whitehall, Henry then struck out on his own grand project. By the time Scrots arrived in England, Nonsuch Palace was in its final stages. It had already proved to be the most expensive by far of the king’s mammoth building projects. It had cost the equivalent of the military campaign in France. In 1546, it was still unfinished although the main courtyards and royal apartments were complete.

Much else was unfinished too in Henry VIII’s last years – the French war had brought Boulogne into English hands – a counter to wager in a future without either Henry VIII and Francis I. From the profits of the Great Debasement, Henry spent lavishly on its defences. But as with Henry’s earlier continental forrays, this one was also indecisive. Similarly, the Scottish War that had promised fulfilment of an ancient English hope – the union of crowns of Scotland and England – had ebbed into something less. The Scots lords had been willing to pledge the sovereign hand of their child Queen, Mary Stewart in marriage to young Edward Tudor under the duress of defeat but by 1546 what was promised on paper had yet to be hand-delivered to London. Mary Stewart and her Scottish crown remained just out of English reach.

A lifetime before all of this, in the early years of Henry’s reign, when Henry’s sister Mary briefly became Queen of France and his other sister Margaret was already Queen of Scotland, dynastic promise and military prowess had, by Wolsey’s conjuration, and for a fleeting moment, proffered the Tudor king a dynastic philosopher’s stone. It was fool’s gold then and so it proved again as the last months of Henry’s reign dawned. Inevitably the old king and his older lieutenants-courtiers like Norfolk, looked back to that world of their youth and their earlier military victories hoped their old dreams might be finally realised. But the younger generation bustling into the foreground and cutting a fresh dash, like the aforementioned Surrey and Seymour brothers looked to a future rising with a new sun-king. These rivals also belonged to to competing elements of a wider political caste that governed Tudor England. These families and their affinities were brought together under umbrelino of court and royal household. At court by the mid 1540s, these families were themselves loosely arranged into factional and cultural interests best described as conservatives and traditionalists on the one hand; and social progressives and religious reformers on the other.

After the turbulence of the 1530s which had seen both the conservative Duke of Norfolk and traditionalist Bishop Stephen Gardiner elbowed aside by the Boleyn and Thomas Cromwell, and upon Gardiner’s return from France, the two men became close allies. United, they proved powerful enough to destroy Thomas Cromwell even as ruthlessly as Cromwell once had destroyed Anne Boleyn and her brother. In the politics of the court they had remained dominant despite the disaster of Catherine Howard’s marriage to the king. The duke and the bishop largely were then content to divide the spoils of influence and patronage between themselves for much of the 1540s.

By 1546 they had been working synchronously for a decade. That is unusual enough of itself to be worthy of comment but this closeness would align them for the remained of their lives.

If the courts of the Early Modern monarchies were made to awe in reality they were as fissile as the elaborate majolica they housed. Religion played its destabilising part in this politics. The central decades of the sixteenth century were to be characterised by increasing political unpredictability not only in England but throughout Europe. Unstable polities of conniving and rival princely dynasties now wore badges of religious faith on their coats, much as Shakespeare imagined the Lancastrian and Yorkist rivals wore their red and white roses on theirs. From the late 1520s Henry VIII’s capricious tyranny had long crazed the polished surfaces of the Tudor court but breaking point was being reached by 1546.

The King’s immobility led him to repeated bouts of rapacious gorging which as the ulcerations on his legs were aggravated by obesity led in their turn to longer periods of painful immobility. Medicinal treatments resulted in repeated cross-infections that weakened Henry’s robust constitution. Often confined to his privy chamber, the Tudor Tyrannus Rex brooded over every slight and his broodnigs magnified the smallest slips. In these uncertain times, little slips counted for much.

As in any court, there was always some semblance of security in numbers. And as England’s premier peer, the Duke of Norfolk had numbers with which to to play and then some. His was the largest noble affinity in Tudor England. When push came to shove, Norfolk could put more men in arms on the field and at greater speed than any other save the king himself. In a crisis, like the Pilgrimage of Grace, Norfolk’s numbers greatly mattered. As Scrots arrived in England it appeared they would also be as decisive 1546 as they had been a decade earlier. However, in uncertain times appearances are most often deceptive.

Bishop Gardiner, by way of contrast to his ducal ally, had but a small personal affinity based about his household as Bishop of Winchester. His influence rested more on his skills than on numbers. In that Gardiner resembled more Wolsey and Cromwell. And like these great ministers before him, the bishop promoted a cotery amongst the able and ambitious. Some were personal trustees like James Basset who remained unflinchingly loyal, through good times and bad; others, like William Paget, would prove less reliable. Principle in Tudor politics was ever a malleable metal and the truly ambitious like William Paget, Thomas Wriothesley and Richard Rich could be bent like tin plate for the gold chains of office.

It was Gardiner’s unmatched diplomatic skill through the 1540s that kept him in preeminence. Ironically, it had been Thomas Cromwell who had shunted the bishop into foreign affairs to keep him out of the way of the king. In the early 1530s a Principal Secretary, Gardiner had been a political threat to Cromwell, partly because the king enjoyed the young bishop’s brilliant wit and partly because Gardiner articulated the king’s religious convictions most ably and closely. However, Gardiner’s initial coolness to Cromwell’s frontal attack on the English church marked his card when the royal divorce had already trumped all suits. Ultimately – perhaps also conveniently for his ambition – Gardiner chose the relative certainty of a Royal Supremacy that guaranteed doctrinal traditionalism over the relative uncertainty of a feckless Papacy which could barely defend its own interests in Italy, let alone champion those of the Ecclesia Anglicana.

Gardiner became the most most coherent and persuasive advocate of the Henrician Supremacy. His book De Vere Obedentia is its manifesto. Once in France, even if Gardiner was apt to lecture the French king, much to Cromwell’s chagrin, the bishop’s light shone ever more brightly. He was the best of advocates, clever and persuasive, and the most supple of diplomats when the mood took him. It was to be the paradox that made his political career. Thus, it was that in the upheavals of the war, Gardiner’s diplomatic agility was vital to an increasingly immobile king. The Bishop of Winchester’s beady-eye missed little.

Whilst Catherine Howard was queen much of the political business at court remained in Norfolk’s hands particularly. But first Catherine Howard’s disgrace and then wars in Scotland and then in France, gave opportunities to a younger generation to catch the king’s eye. In war reputations are quickly made and quickly lost. A new generation of soldier-politicians led by Henry Howard, Earl of Surrey, Edward Seymour, Earl of Hertford and John Duley, Viscount Lisle and Edward Seymour’s younger brother, Thomas who unlike he dour elder brother, was all dash and dazzle, made their splashy entries into the court and politics. Both the Seymours were uncles to the heir apparent, Prince Edward. The Seymours looked to Prince Edward’s future, as his future as king was dynastically entwined with theirs as kin. Surrey’s politics looked rather to the Howard hegemony and Gardiner’s brilliance.

After 1544, there were also new relatives of Henry’s last wife, Catherine Parr come to court. They rose to prominence with her marriage to the king. Queen Catherine’s genial brother William Parr had already made his way in court being elevated in 1543 to the earldom of Essex – previously Thomas Cromwell’s plum. William Parr was one of nature’s clippers tacking ever to the dominant tide. Later in Edward VI’s reign, the young king described him as his “beloved uncle”. By 1553 Parr would be Marquess of Northampton. If only step-uncle to the king, he stepped-up the ladder of the political the elite by virtue of his sister’s marriage. As a member of the royal affinity William Parr therefore held high office in the royal household throughout these years. Edward VI’s court turned out to be a place for uncles of one sort or another – another sort was a much less genial man than William Parr – Sir Michael Stanhope, step-brother of Anne Stanhope who was second wife of Lord Protector Edward Seymour and from February 1547, Duchess of Somerset. Stanhope found his way into Edward’s Privy Chamber but he was alike his Seymour kin, he was never to enjoy the epithet “beloved uncle” from his royal charge.

And it was behind the closed doors of the privy chamber that momentous events were played out in the last year of Henry VIII’s reign. Behind those closed doors two other men made political weather – Sir Anthony Denny, long Principal Gentleman of the Privy Chamber and Sir William Herbert (married to Anne Parr, the queen’s sister) who was made up to Principal Gentleman from 1546. Denny and Herbert managed access and much more. They managed the Dry Stamp that wielded the royal name and its executive function. Deny himself had married Joan Champernowne in 1525, a close friend of Catherine Parr from the time of her first marriage. Denny and his wife may well have played an instrumental part in reintroducing the widowed Catherine to the prematurely aged king.

By the end of 1546 Scots had painted a number of these luminaries of the English Court – famously, Queen Catherine Parr (left); Henry Howard, Earl of Surrey as previously noted, and young Edward, Prince of Wales, later King Edward VI. Alike Holbein earlier, Scrots fortuitously painted these men and women at the breaking of a wave that was destined forever to change England’s political landscape. His portraits paint their own picture of this tumultuous time.

Catherine Parr as can be seen is resplendently accoutred for her portrait. She sported the latest fashion but Scrots also catches something else. Whilst avoiding our gaze, his Catherine appraises distant horizons with a penetrating stare. Her marriage to the Tudor colossus was not everything she had wanted from life or indeed from marriage but she settled for the position it bestowed upon her and as importantly upon her family and kindred. That of itself speaks to the heart of calculation. She sought an active political position for herself and a brief term as Regent during the French wars whetted her political appetite. Her eyes too gazed upon the young Edward. Perhaps another regency has already loomed in her distant field of vision?

As intelligent as ambitious, Catherine Parr, like Anne Boleyn before her, was sympathetic to the causes of religious radicals. Like Catherine of Aragon, she owned practical savvy and had thus served with distinction as Regent in the last phase of the wars with France – whilst Henry was in France masterminding or overseeing at least the grand campaign which ended with the capture Boulogne. Unlike Anne and more like Catherine of Aragon – Catherine Parr had an even temperament. As queen she quickly became a leading light amongst the court’s Humanist intelligentia – something of a patroness both of men of letters and of education more generally. She was almost of an age with Henry’s eldest child – only four years older than the lady Mary – and the two in fact enjoyed a warm relationship at least until after the death of Henry VIII in January 1547. This closeness to Mary had enabled Catherine to facilitate a rapprochement of sorts amongst Henry’s three children, who were all named in the Succession as determined under the king’s will. Her initiative led to a family project to translate the Erasmus Paraphrases of the Gospels and notably Mary translated St John’s Gospel whilst Elizabeth assisted with the paraphrase of St Luke’s. It was from the Magnificat in Luke’s Gospel that Elizabeth was famously quoted on her accession in 1558.

When the Paraphrases had first been published in 1524, praise had been heaped them and upon their author, Desiderius Erasmus. The Paraphrases were quickly a fashionable accoutrement of every noble household in Europe. However, by the later 1540s much Humanist endeavor that once had been perfumed by scholarly orthodoxy, came to be seen as part of the crazy-paving that led to heterodoxy and hell. The Paraphrases fell victim to this process. However, the royal translations were published in 1548 in Edward VI’s reign, under Cranmer’s archiepiscopal imprimatur. The endeavour itself speaks to the fact that even in the dolour days of Henry’s last years the Ecclesia Anglicana remained wedded to that movement of Catholic Reform that belonged to Erasmus and Fisher as much as to More and Gardiner.

It might therefore be said that Catherine Parr’s project offers historians a pin with which to unpick something of the true character of Mary I’s faith. As did her father and mother, Mary belonged emotionally, intellectually and spiritually to the culture of Catholic Reform – a intellectual predisposition she later shared with her kinsman and future archbishop of Canterbury, Cardinal Reginald Pole. It was those beliefs that animated her religious policy after 1553 as much as her personal piety in public and private. Her Church was to be both one of doctrinal restoration and spiritual and institutional reform. It also, coincidentally, demonstrates that Mary’s Latin was more than serviceable. It really knocks on the head that recent historical prejudice formulated by Professor Geoffrey Elton, that Mary was linguistically dumber than average as well as an unintelligent, narrow-minded bigot.

But if Catherine Parr’s influence in the royal family was largely benign, she harboured ambitions beyond that of royal stepmother and editor of translations. From her marriage to Henry VIII, Catherine Parr’s patronage of reformers had made her vulnerable to the traditionalist groupings at the court as yet clustered around those two dominant figures: Bishop Stephen Gardiner and Thomas Howard, Duke of Norfolk.

The Howards – as dukes of Norfolk – had become under the Tudors England’s leading noble family. They had enormous land-holdings predominantly in East anglia and London. Theirs was a large affinity built up over the previous sixty years. No peer could put more men in arms that the duke of Norfolk. The Howards purveyed two wives to Henry VIII – Anne Boleyn and Catherine Howard were both of the ducal family. Thomas Howard’s youngest daughter, Mary, had married Henry Fitzroy, Duke of Richmond – Henry VIII’s bastard-son by Elizabeth Blount. Richmond was very much in awe of Henry Howard and the two were close. There had been heady talk of Richmond being king but he had died early, leaving his neglected wife Mary a penniless widow. But, overlooked perhaps in marriage, young Mary was not entirely powerless. In due time the dowager Duchess of Richmond would play her own small part in the events which destroyed the Seymour in 1552 but not before she did for her own brother in 1546.

For all their eagerness to marry into the Tudor dynasty, Howard ambition had only Anne Boleyn’s daughter Elizabeth – by statute a bastard although named in the succession in Henry VIII’s will – as an asset in the games of succession that were about to commence. In 1546, as assets went, Elizabeth was worth less: in the line of succession she stood behind both her half-brother Edward and her half-sister Mary and as the product of the Boleyn marriage, hers was the least legitimate of the blood claims. Unsurprisingly, therefore, having once married with a bastard Tudor to no great effect, the Howard dynasty looked to legitimate lineage for its greater glory.

The ducal heir, Henry Howard, Earl of Surrey, was the family pride. He was painted in his pomp by Scrots in the course of 1546. Surrey was a star at court – an established figure in the English Renaissance and a talented poet – he had been Captain General of the army in France and had become something of a flashily successful if flamboyant military figure. From his equally flamboyant palace, Surrey House, on the edge of Norwich, Henry Surrey reached out to touch forbidden fruits – perhaps perceiving himself alike the queen to be the stuff of which future Regents are made. Given his high status – an almost once and future king – the once being the days of chance immediately after Henry VIII’s death – many impossible dreams were possible for him.

Especially for a Howard these would be dangerous dreams to dream but for Henry Surrey they were more dangerous still. His mother, Elizabeth nee Stafford, was daughter of the attainted Duke of Buckingham.

Scots portrait catches the swaggering charm and charming vanity and something of Surrey’s charisma but little of the restless sensitivity he reveals only in his poetry and other writings. A lover of sonnet, he wrote sonnets for lovers. The rare beauty of sweet Geraldine Fitzgerald were amongst the courtly charms that moved his pen. A lover of art, architecture and heraldic devices, he was very much a Humanist scholar and Renaissance prince. Surrey House which features in the background of the last grand portrait, was the apotheosis of those dreams.

Interestingly, unlike many at court, Henry Howard inspired loyalty. After his sudden arrest, Hugh Ellis, his secretary maintained Surrey’s innocence to the end and under relentless questioning. That is of a piece with the poet – Surrey wears on his sleeve a beguiling direct inner emotion which has a startling honesty and clear sightedness – but qualities that betoken charm in poetics can betoken recklessness in politics. Sensitivity can make one as apt to pick up the sword as the pen. Henry Howard in his time freely wielded both.

The grand portrait finely composed by Scrots but probably with a deal of input from Surrey himself bears the motto: Sat Super Est – enough survives. The the factions coalescing around the Seymour in the second half of 1546 had long decided they could not afford for the Howard dynasty to survive. However, more Brutus than Cassius, Surrey was too noble for skulduggery.

The Tudor Court in 1546 was full of men and women far less squeamish than Henry Howard. And so cometh the crisis cometh the men….and as exeunt the Howard and then Henry VIII himself, so enter the Seymour with the Stanhope in their capacious train…

Part II: The Art of the Possible – the crisis of 1546.