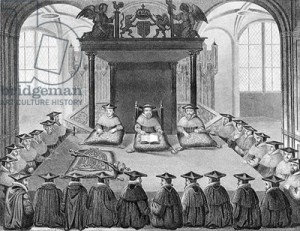

Majesty & Magsterium – the 1530’s

Whether it was a collective loss of nerve or whether it was conviction – the submission of the Convocation of the Clergy of Canterbury in February 1531 was the turning point, indeed arguably, even if that argument is unfashionable, it was the point of no return. It marked a clear end if not unambiguously a new beginning.

Still in 1530 the church in England was composed of two convocations which represented the clergy in the two metropolitan Sees – Canterbury and York. The two were to all intents and purposes independent of each other; both represented the episcopate and parochial clergy; both convocations also included mitred abbots, priors and other senior representatives of the regular clergy who belonged to a hierarchy parallel to the secular clergy. The latter group were directly responsible in all matters of discipline and ministry to their local bishop and to the local church courts. They lived with and under the competing jurisdictions of civil and canon law. The regular clergy – that is those in religious orders – monks, friars, priors, canons regular, lay brothers, nuns and such – were disciplined by their order’s rule; they were responsible to the orders’ hierarchies of superiors and to the orders’ fathers-general usually resident in Rome; the code of canon law which governed them was also distinct; but ultimately – and this is vitally important – all the regular clergy were subject directly to the pope who acted in loco parentis as their bishop.

The division between secular and regular clergy was more than a organisational nicety dressed-up in a habit. The two arms of the church performed distinct functions in the medieval church. The secular clergy served the laity and brought to them the sacraments which were the seal of grace, bestowed by Christ on the faithful and which only the clergy could bestow upon the laity. The regular clergy served God though prayer. In particular they prayed the hours, the daily prayer of the church that was by the ninth century set out in the breviary; they prayed, on their own behalf, on behalf of the entire body of the faithful, living and dead. Their singular devotion to the grace of perpetual prayer enabled others of the faithful to enter heaven. To borrow a contemporary analogy the regular clergy acted like a bank of prayer upon which the entire body of faithful could draw and whose grace might be used to mortgage any soul, indeed all souls, from the penalty of sin. Central to that life of prayer, over and above the church hours, was the church’s ultimate prayer – the Mass. And it was to that latter ultimate good work that another group of medieval clerks were wholly devoted. From the late fourteenth century, particularly in England, chantries, largely founded by laymen, were endowed to secure a priest to say the efficacious prayer of the Mass for the soul of the dead departed and for his or her intentions.

Immediately it is possible to see that this structure is dependent upon a particular view of grace and salvation. And that division of clerical labour had, time and again…continued here….