Who was the Cardinal of Lorraine; what was the Council of Trent; and, why should you care?

The first question is most easily answered.

The Cardinal of Lorraine is the title of Charles de Guise, second son of Claude Duc de Guise and Antoinette de Bourbon. His elder brother Francois succeeded his father as duke whilst his elder sister, Marie de Guise, married James V of Scotland. She is the mother to Mary (I) Queen of Scots and she is also Regent of Scotland from 1554 until her death in 1560. As a consequence of the marriage into the Scots royal family the Guise became Prince étranger at the court of France. From his earliest years Charles was universally recognised as the brains of the family. He was Duc de Chevreause and Archbishop of Reims.

The Guise were a cadet branch of the house of Lorraine. The family was proud of its ancient lineage and the House of Lorraine traced its ancestry directly back to the Frankish kings. In due time the Guise descendants were destined not only to include James VI and I of Scotland and England but also Henri IV of France. They were related to the Bourbon Kings Louis XIV, Louis XV and Louis XVI (and, after 1700, also the Bourbon kings of Spain). Later in the eighteenth century Francis III of Lorraine married Maria Theresa heiress of the House of Hapsburg. As a consequence Francis was elected Holy Roman Emperor. The children of Emperor Francis I and Empress Maria Theresa establish the House of Hapsburg-Lorraine and include Emperor Jospeh II; Emperor Leopold; Archduchess Maria Antonia who marries Louis XVI and is known to history as Queen of France Marie Antoinette. Their grandchildren will include Emperor Francis II and their great great grandson will be the Emperor Franz Joseph who ruled Austria-Hungary from 1848 until the disaster of the First World War (1914-18).

Charles de Guise was a favourite in both the courts of Francis I and Henry II. He played a significant part in the education of Henry II and was rewarded for his efforts. Yet for all his aristocratic hauteur unlike many of his class he did not hunt, nor gamble, nor feast. He said Mass regularly; he preached as regularly and became rather famous as a rhetorician; he fasted twice each week kept a liberal table for guests over which he presided with ostentatious abstemiousness. Still for all his personal restraint he was a prince of the church in the grandest style and a holder of multiple benefices – bishoprics and abbacies.

After several attempts he was finally raised to the dignity of cardinal by Pope Paul III (Farnese) in 1547. His church in Rome was that of St Cecelia. For most of his career after 1547 he was both Cardinal and legatus a latere. Briefly the principal minister of France in the short reign of Francis II – who was the first husband of his niece, Mary Queen of Scots. The Cardinal of Lorraine was also by then the most powerful if not the most senior member of the French episcopate. He played a prominent role in the suppression after the conspiracy at Amboise and later in the Colloquy of Poissy. As cardinal he participated in the conclave that elected Julius III ( del Monte) and attended the closing sessions of the Council of Trent in 1560s.

This brings us neatly to the second question – what was the Council of Trent?

The religious tremor fired by Luther nailing his ninety-five theses to the door of Wittenberg Cathedral set off a tsunami of doctrinal reformation. It quickly over-ran the narrow straits of indulgences and breached the doctrinal framework of the Western church. The inundation of was so complete by 1530 that it was difficult any longer to discern orthodox from heterodox – the reformers themselves being as divided from each other as from the old religion they so vigorously assailed.

As the initial tumult receded the religious landscape of Europe was entirely changed. The world of belief looked and felt different. Some stragglers clung desperately to the wreckage of the lost certainties; others sought to accommodate themselves to the changed landscape of ideas; others yet saw this as the moment to strike down the old ways and build a new confessional structure; others still, saw this as an opportunity to reforge orthodox doctrine into a militant creed.

Therefore, not all those we might call ‘reformers’ were heterodox in doctrine; and, neither were all the doctrinal traditionalists orthodox in practice and discipline. The confusions and the over-lapping opinions about theology made for uncertainty. Amongst all the Christians in the West the competing explanations of the meaning of Christianity quickly beggared belief. The traditional language and philosophical framework of medieval theology and the old rituals of masses; Te Deums; and processions, was inadequate in the face of the challenges posed by the clamour of new ideas.

And on both sides those who led the ensuing debates – Calvin, Bucer, Zwingli, and Cranmer on one side; Pole Contarini, del Monte; Loyola; Neri and Borromeo on the other – sought both to codify and to clarify Christian beliefs in fresh language. The faith of individuals; families; affinities; cities; regions and even nations were challenged as all men and women of the age groped towards a different understanding of Christianity – the religion and belief structure which had for a millennium stood unquestioned in the centre of Euoropean society, culture and politics.

Paul III (Farnese) convoked the Council at Trent as a response to the challenge. The old man was in a hurry. Farnese exemplified that oldest of papal stories – the stop-gap – elected to please everyone – who turned out to be the agent of profound change. There is a wonderful portrait of Paul III painted by Titian – it catches something of his magnetism and sly craft.

Paul III (Farnese) convoked the Council at Trent as a response to the challenge. The old man was in a hurry. Farnese exemplified that oldest of papal stories – the stop-gap – elected to please everyone – who turned out to be the agent of profound change. There is a wonderful portrait of Paul III painted by Titian – it catches something of his magnetism and sly craft.

Historically Ecumenical Councils of the Christian Church were summoned to deal with major crises. Trent was no exception. The Council of Nicea had long set the gold standard for such gatherings – summoned, by the Pope; the Patriarchs; and, the Emperor Constantine, to determine the nature of Jesus as God and Man it ended by famously rejecting the Dualist doctrines espoused by the majority of bishops led by Arius of Alexandria. Even today Christians of most denominations still recite its Formulary or Nicene Creed in their religious services.

Paul III’s hope – and that of most of the hierarchy at the time – was to find another similar formulation which would reunite the radicals with the traditionalists. After Wittenburg, Luther had been the first to appeal to the authority of an Ecumenical council over the hierarchy of bishops and pope. At first the papacy resisted this demand. The secular princes of Europe sought to find their own solution – particularly after the Peasants revolt in Germany in 1524. But the reformers and radical evangelists – whose refusal to accept the restrictions imposed in 1529 by the Diet of Speyer led the famous ‘protestio‘ that later gave the shorthand name of Protestants to the various groups of reformers – refused to compromise with the secular authorities.

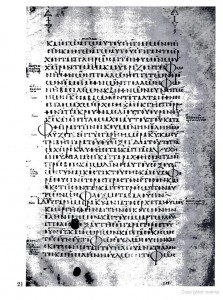

This refusal led to a clamour for a council and finally Paul III conceded the principle but then found himself unable to persuade the reformers to attend. Thus, the council that finally assembled in Trent in 1545 was poorly attended and always looked doomed to certain failure. The Council of Trent met in three principal active convocations: 1545-7; 1551-2; 1561-63.. it met over almost twenty years; each convocation was of tremulous uncertainty, and yet it turned into something altogether different but no less radical than for which the reformers had hoped. And its decrees defined what we call today the Roman Catholic Church and provided the intellectual foundation of a movement history knows by another familiar shorthand – the Counter-Reformation.

And that movement in turn shaped European history and it its turn the history of the wider world that fell under European domination in the nineteenth century. Moreover, these confessional divsions and rivlaries played out in the events that shaped the modern age. Even today in the United States the cultural and racial divide in America between the Hispanic community and the White community and the Black community bears witness to the scars of that confessional divide.

And it was to Trent that the Cardinal of Lorraine went in its final last session in the 1560s in a last gasp attempt to find the words that would paper over the divisions in Christendom. The Cardinal of Lorraine Charles de Guise was by then one of the more familiar figures of the sixteenth century. He might almost have been the incarnation of the very sort of churchman held as an exemplar of the good and bad in the institutional church.

Lorraine’s high position has been long held in as low esteem by History as his sincerity was certainly doubted by his contemporaries. A worldly statesman and a worldly churchman – like Thomas Wolsey – he was dominant in his time. Like Wolsey he received a poor review from contemporaries for his efforts to finds words of accommodation. He was suspected by both sides of belonging to the wrong side. Later the nationalist historians of the nineteenth century who composed Europe’s great narrative histories saw Lorraine – and indeed Wolsey – as tainted goods – too politique to be men of God; too clerical to be men of vision. According to the received wisdom the Cardinal of Lorraine accumulated office and wealth on a scale prevoiulsy unkown but squandered it on lost causes and self-aggrandisement – again drawing the obvious comparison with Cardinal Wolsey.

Thus narrative historians of the nineteenth century pigeon-holed them; thus they have remained – despite the revisionism of the later twentieth century. But one man has seen more than the sum of their parts – an historian, Outram Evennett.

Evennett became known to me when I was an undergraduate. I think his book the Spirit of the Counter-reformation may have been on a course I studied under Anthony Wright – who has only recently retired from the School of Hsitory at Leeds. He also wrote a wonderful pamphlet for the CTS (Catholic Truth Society) The Reformation. It remains one of the best things ever written on the subject. In a mere thirty one pages of pure gold and purer insight Evennett gives more of a sense of the events than many in a hundred times as many pages.

Evennett was not a man who published a huge amount although I understand he was a fine teacher and lecturer for many years at Cambridge. He belonged to that generation of historians who went reluctantly to print; always believing that understated reflection made for better historical understanding than the verbosity of the publishers’ plenty. Fashions change and these days no career in any academic discipline is worthy of note unless it has been trailed in many words across many learned journals; recycled in yet more sentences in many a monograph and finally committed to flattering footnotes in scholarly commentary by kind colleagues.

Evennett understood religious history as few men before or since. He comprehended the world of sixteenth century debate. He valued the contributions from Reformed and Catholic because he could measure them in their own terms and their own times. His writing is lucid. He grasped all the terminology and read the debaters in their own languages and in their Latin lingua Franca. Above all Evennett did not see either side through the prism of our contemporary liturgical reforms and the post 1960s accommodations of ecumenism which have blurred distinctions and made the differences appear as if they were without distinction or meaning. Whilst that may have be a desirable religious end for modern Christian society in its present sense – it doesn’t asssit the historian to understand the nature of the events five hundred years ago and all that would flow from then and why.

The primary colours of the religions painted by the bold strokes of Evennett’s pen may not suit the modern eye. Many may be uncomfortable with the detailed debates about the meaning of real presence that comes to animate the religious turmoil from the mid sixteenth century on – but that is the real world where we can locate the animating spirit of religious reformers like Calvin & Peter Martyr; like Reginald Pole and Cardinal Caraffa.

These were the terms of the debates that animated the political discourse and shaped the religious philosophy of Western Europe. In time they were the debates that divided Europe into Catholic and Protestant. In time men fought for these beliefs and in time men and women died for them in great number. In time too they would come to inform our sense of nationality and over time the very secular philosophies of the Enlightenment and Marxist dialectic were partly shaped in response to the trauma that flowed from the confessional divide shaped by events in the hundred and fifty years between Luther’s emergence and the Peace of Westphalia at then end of the Thirty Years War in 1648.

Evennett does that most extraordinary thing – he really draws out the nature of the distinctions between the doctrinal beliefs of Roman Catholic and Calvinist, particularly surrounding the doctrine of the real presence which are central elements to that greater story. And in telling that story through the politic shuffling of the Cardinal of Lorraine and the final attempt at the Colloquy at Poissy to find an accommodation of words – it appears now that the very men whose lack of principal and willingness to compromise – for which they were excoriated by nineteenth century historians – might yet seem to scholars of this twenty first century to be almost heroic labours.

And that in itself reveals something of the uncertain nature of History. We tend to regard History as a dry science full of dead dates that populate its great periodic table of chronology. In fact history is something quite different. It is more the art of seeing beyond ourselves; beyond the foreground of the here and now where we live to the detail on the background, caught in the half-light of a few surviving documents. It is that sense that best informs history. It is that fleeting image that shows us from where it is that we truly have come.

Niall Ferguson who is nominated by Secretary Gove to look at the History Curriculum should take note: this book by Outram Evennett should be on every history undergraduate’s syllabus. Sadly it is far too scholarly to appeal to the likes of Professor Ferguson.

For Niall Ferguson and those media historians like him are intellectual poseurs whose trade is the flashy ephemera of the passing fad. The patient craft of the historian is to better understand the past. The demagogue uses a version of the past to proselytize about the present pretending it will determine the future. These silly, linear simplicities are merely rhetorical devices: they are empty, shallow; anodyne and unworthy of note. They certainly must not be mistaken for scholarship – let alone History in any proper or meaningful sense..