A rough guide to the wars of the Roses –

Burying King Richard III

Burying King Richard III

Laying to rest the earthly remains of Richard III seems to have dug up a lot of a-historical nonsense long buried by good historical research. In the best of traditions the pantomime image of the hunchbacked Richard III has turned out not to be that far from the physical reality. Richard was indeed a hunchback. We have been breathlessly told this certainty would change history. Unsurprisingly, it has done no such thing. What the blizzard of Media interest did reveal was the depth of the shallows of common knowledge about England’s history.

King Richard III remains have been was re-interred in Leicester Cathedral with what passes these days for pomp, circumstance and – as the late Kenny Everett might have said – “and all in the best possible taste”. A royal duke; a royal countess; a Cardinal Archbishop; and, even the Archbishop of Canterbury were present to make history before our eyes. There was a a phalanx of Media historians as learned outriders. Revelations were promised. The circus has left Leicester. Gone and as easily forgotten as these events deservedly may be they have left me wondering whether anyone was really any the wiser from all the juggling of names and dates and all the clowning about in period costume.

King Richard III remains have been was re-interred in Leicester Cathedral with what passes these days for pomp, circumstance and – as the late Kenny Everett might have said – “and all in the best possible taste”. A royal duke; a royal countess; a Cardinal Archbishop; and, even the Archbishop of Canterbury were present to make history before our eyes. There was a a phalanx of Media historians as learned outriders. Revelations were promised. The circus has left Leicester. Gone and as easily forgotten as these events deservedly may be they have left me wondering whether anyone was really any the wiser from all the juggling of names and dates and all the clowning about in period costume.

As I’ve vociferously complained about the silly things that have been said on Channel 4 and elsewhere I have asked myself could I do any better?

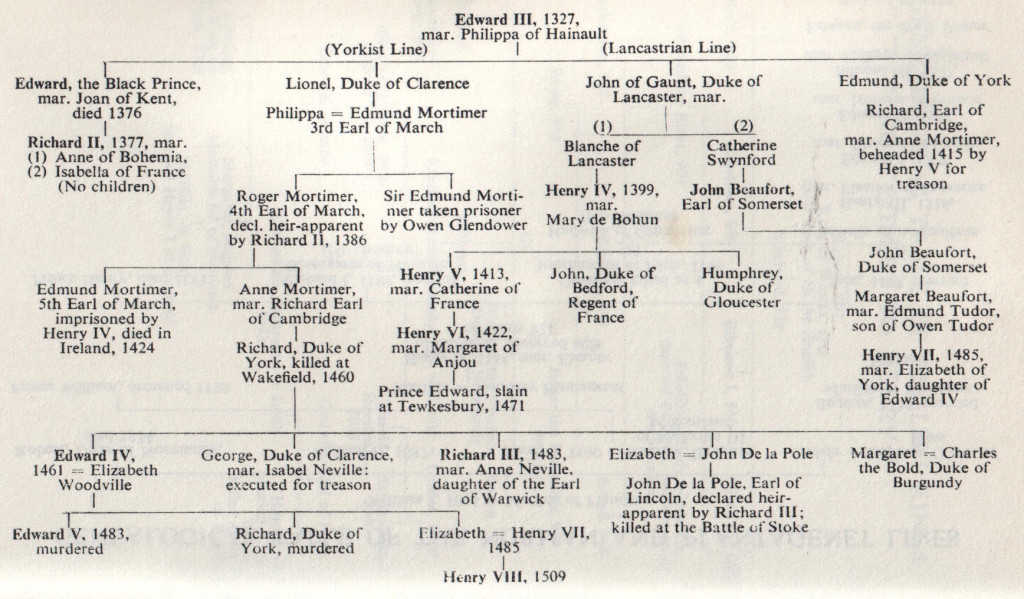

Best beloved, you must decide that for yourselves – here’s my Rough Guide to those pesky Wars of the Roses and the Plantagenet – of whom Richard III was only the last rose of the House of York’s once glorious summer.

Part I: The Wars and the Roses:

The wars in question are more a series of military engagements fought by various cadre of various branches of a single royal family or dynasty – Plantagenet – in the last decade of the fourteenth century and again the middle decades of the fifteenth century. They are taken to have ended in Bosworth Field in 1485 and with the death of Richard III and the accession of the first Tudor – Henry VII.

However, as there was no formal beginning to these so-called wars it should be no surprise that their ending was as similarly informal. The end date of 1485 was only formally noted from the lofty retrospect afforded from the theatrical stage in the 1590’s as set by William Shakespeare. By then another sun was setting on the last of another dynasty – one that had made it largely because of the Wars of the Roses – the Tudors – for by the 1590’s the last Tudor, Elizabeth I, short of hair and long on make-up was long beyond child-bearing. Elizabeth was already making way for the progeny of her longtime rival Mary, Queen of Scots. That is another history….back to the Roses….

As these Wars of the Roses were largely bitter fruits of family feuding in that sense they partly and genuinely resemble the TV series Game of Thrones which took its inspiration from them.

The roses in question are red and white: the red rose is for Lancaster and the white rose is for York. These badges still survive in their respective county emblems to this day. The roses came to represent two cadet branches of the one family – the Plantagenet – for these wars were nothing if not an entirely family affair.

Their choice of roses of two colours as a badge of their conflict went back to a law case and subsequently to a confrontation in Temple Garden between the litigants. Its dull prose are poetically repainted in Shakespeare’s Henry VI, Part I: Act II, scene iv which itself symbolically portrays this occasion as the origin both of of the Wars and of the Roses. Richard Plantagenet (the figure on the left) who eventually became the Duke of York; Lord Protector and legal heir apparent to Henry VI, plucked a white rose as the emblem of his family branch, York; and his adversary, John Beaufort, Duke of Somerset (the figure on the right), picked a red rose as the badge of the other branch, Lancaster.

Their choice of roses of two colours as a badge of their conflict went back to a law case and subsequently to a confrontation in Temple Garden between the litigants. Its dull prose are poetically repainted in Shakespeare’s Henry VI, Part I: Act II, scene iv which itself symbolically portrays this occasion as the origin both of of the Wars and of the Roses. Richard Plantagenet (the figure on the left) who eventually became the Duke of York; Lord Protector and legal heir apparent to Henry VI, plucked a white rose as the emblem of his family branch, York; and his adversary, John Beaufort, Duke of Somerset (the figure on the right), picked a red rose as the badge of the other branch, Lancaster.

In Shakespeare’s play their followers then choose sides by plucking a red or white rose. This dramatic conceit works brilliantly on stage but is clouds a darker dynastic reality – the conflict reignited in Temple Gardens had its origin in an earlier act of regicide, when the son of the Duke of Lancaster (John of Gaunt’s eldest son) known as Henry Bolingbroke after the castle where he had been born, first had pushed aside Richard II; and then later almost certainly had the king murdered. Henry Bolingbroke succeeded Richard II in 1399 as Henry IV – and he was the first king of the House of Lancaster. His claim was always questionable and had always left many awkward questions of legitimacy unanswered. These questions were decisively but deceptively answered by Henry IV’s son, Henry V, in his victory at Agincourt but they resurfaced after Henry V’s untimely death in the political tensions during long minority of Henry VI.

The Royal Houses of Lancaster and York were therefore both branches of family Plantagenet. They respectively each took their names from the royal duchies of the two principals in this bloody struggle for the throne. Edward III had originally bestowed these titles on his younger sons. This is why they are described as the cadet branches of the same royal house or royal family. They are the junior lines to to the senior established line of succession just as today Prince Andrew and Prince Edward are the juniors to the senior line of their elder brother, Prince Charles. Similarly, Edward III’s eldest son (another Edward) was eldest son and heir to his father. He was nicknamed ‘the Black Prince’ because in battle he wore a black ostrich plume in his helmet. He had taken ostrich feathers or plumes to be part of his coat of arms as Prince of Wales (and heir apparent) when his father created the order of the Knights of the Garter and made his son the premier garter knight. To this day ostrich plumes have remained part of the regalia of any Prince of Wales.

Family Plantagenet

The family name ‘Plantagenet’ like the family name ‘Windsor’ was not originally a family or surname. It was a nickname. It not until the mid-fifteenth century that it was actually adopted as a family name – and then – and initially – only by one of the two principal protagonists: Richard, (3rd) Duke of York. Before then children of the Plantagenet royal dynasty were generally named after the place of their birth: for example – Edward of Woodstock (Prince of Wales – the Black Prince); Lionel of Antwerp; John of Ghent (i.e. Gaunt). Women heiresses by contrast often took the name of their noble house – Eleanor of Aquitaine; Blanche of Lancaster.

By the time the Yorkist branch adopted the family name Plantagenet in 1450 the struggle between Plantagenet royal cousins and their kindred already had been underway on and off for almost sixty years.

Plantagenet the Name

Plantegenest (Plante Genest) had been a 12th-century nickname of Geoffrey, Count of Anjou who commonly wore the flower on his hat or coat. Count Geoffrey married (Empress) Matilda who was the only child of the last Norman King of England, Henry I, who was himself the fourth son of the William the Conqueror (William I).

Plantegenest (Plante Genest) had been a 12th-century nickname of Geoffrey, Count of Anjou who commonly wore the flower on his hat or coat. Count Geoffrey married (Empress) Matilda who was the only child of the last Norman King of England, Henry I, who was himself the fourth son of the William the Conqueror (William I).

Count Geoffrey was Matilda’s second husband. Matilda’s first marriage to the Holy Roman Emperor Henry V had been childless. Hers was a title therefore above all titles and her children by Geoffrey bore the nickname ‘FitzEmpress’ (son of the Empress). Their eldest, Henry FitzEmpress, had another nickname Curtmantel (short coat) from the cut of his coat. However, generally, he is simply known as Henry II of England.

In addition to England and Normandy from his mother Henry II inherited Anjou, Touraine and Maine from his father Geoffrey; and shortly thereafter he acquired by marriage the lands of the duchy of Aquitaine by marrying its heiress, Eleanor, Duke of Aquitaine in her own right and sometime Queen of France. Altogether these lands in England and France – to which Henry II in due course added parts of Ireland, Brittany, the Vexin and parts of Southern France – comprised the Angevin Empire.

Therefore, Henry II (1154-1189) is England’s first Plantagenet king.

The Plantagenet Dynasty:

The Plantagenet kings are commonly taken to compose four different houses or dynasties in history’s book: The Angevin; The Plantagenet; The House of Lancaster; The House of York.

Henry II & Eleanor of Aquitaine; foreground Richard I. In the same abbey at Fontevraud are buried the hearts both of King John and his son Henry III.

1. The House of Angevin: the Angevin kings are Henry II – and his sons, King Richard I (the Lionhearted) and King John. After the death of Henry II Kings Richard and John embarked on high risk, high tax polices which duly lost the family of most of its French possessions and as Henry II’s Empire collapsed, the barons became ever resentful of royal demands on their incomes. The stand off between crown and nobility was nominally settled by Magna Carta but even after making all these concessions King John struggled to hold on to the English throne. His sudden death accidentally secured the realm for his infant son, Henry III.

2. The House of Plantagenet: this is the main line of the succession of English kings which runs from King John’s baby son and heir Henry III (1216-72); to Edward I (1272- 1307); to Edward II (1307- deposed Feb 1327 d. Sept. 1327 ); and gloriously to Edward III (1327 -1377); and finally to his grandson Richard II (1377- deposed 1399 d.1400).

3. The House of Lancaster: there are as we have seen three kings of the House of Lancaster: Henry IV ( Henry (of) Bolingbroke 1399-1413); Henry V (1413-1422) and famously the victor of Agincourt and King of France; and his son by Katherine of France, Henry VI (1422 -1461) (1470-1471 – imprisoned in the Tower d.1471).These three kings are the central figures in the Shakespeare history plays named for them and they played a very important part in shaping the political imagination of England’s governing class from Tudor times onward.

4. The House of York: there are three kings of the House of York: Edward IV; Edward V; Richard III. These too feature prominently in Shakespeare’s history – mainly in Henry VI Parts II & III and naturally enough in King Richard III, famously (over)played by Lawrence Olivier on film.

The Rival Claims:

The House of Lancaster and the House of York were as aforementioned both cadet branches of the main Plantagenet line of succession. The dynasty as can be seen from above already had had its troubles from time to time – with King John and then more notoriously with Edward II. However, everything had seemed to come good and heaven smiled on the monarchy of Edward III.

Edward III in his long reign re-made the Plantagenet dynasty afresh. he gave it a distinctly English image. Edward III was shrewd in marriage and politics: cautioned as he was by his father’s homosexual foibles; tutored as he was by his father’s failures; and later schooled as he was under the the presumptions of his mother’s lover – Roger Mortimer, Earl of March – the very man supposed to have arranged his father’s (Edward II) death with the infamous red hot poker, Edward III understood the rules of the game of thrones better than any of his family.

Edward III in his long reign re-made the Plantagenet dynasty afresh. he gave it a distinctly English image. Edward III was shrewd in marriage and politics: cautioned as he was by his father’s homosexual foibles; tutored as he was by his father’s failures; and later schooled as he was under the the presumptions of his mother’s lover – Roger Mortimer, Earl of March – the very man supposed to have arranged his father’s (Edward II) death with the infamous red hot poker, Edward III understood the rules of the game of thrones better than any of his family.

Edward III set aside tutelage of his mother and her upstart lover and despite his mother’s plea “fair son, have pity on the gentle Mortimer” Edward had gentle Mortimer ignominiously hanged at Tyburn. Edward III was not a prince to be sentimental about old family friends and ties of blood.

Edward III made a sound marriage to Phillipa of Hainault. His wars with France regained territories long lost to the Plantagenet dynasty. But Edward III reconquered those lost lands in France as King of England. This was an English Empire not an Angevin Empire restored. The wars he thus initiated became known as ‘The Hundred Years War’. The booty and the lands in France made the English nobility rich and by this means Edward III kept them engaged in his foreign enterprises – much as Louis XIV was later to do in France. It also gave the king a free hand to do as he wished in England.

By his marriage to Phillipa of Hainault Edward had a string of children most of whom unusually survived to adulthood. His eldest son, “the Black Prince” Edward, Prince of Wales became the principal agent of the dynasty’s political project in France. His chivalrous image as a knight of the garter; as the hero of Crecy, Poitier and Reims; disguised the fact he was something of a brutal thug. In France “the Black Prince” fought a string of military campaigns as notable for their violent savagery and as their strategic brilliance. He married his cousin Joan of Kent – herself a direct descendant of Edward I – by whom he had two sons Edward of Angoulême and Richard of Bordeaux. All then seemed set fair when the young Edward of Angoulême died suddenly in 1375. As so often in royal history, one dynastic tragedy was followed by another.

By 1375 the Black Prince himself had long been plagued by what may have been recurrent bouts of amoebic dysentery acquired on campaign in Portugal. The Black Prince died in 1376. He was buried in Canterbury Cathedral. His effigy and tomb have become an archetype for his age. Then in 1377 Black Prince’s father Edward III as suddenly quickly followed his eldest son to the grave.

By 1375 the Black Prince himself had long been plagued by what may have been recurrent bouts of amoebic dysentery acquired on campaign in Portugal. The Black Prince died in 1376. He was buried in Canterbury Cathedral. His effigy and tomb have become an archetype for his age. Then in 1377 Black Prince’s father Edward III as suddenly quickly followed his eldest son to the grave.

Suddenly the dynasty was left in the insecure hands of the ten year old Richard of Bordeaux. He succeeded his grandfather Edward III in 1377 as Richard II. By culture and education and outlook the boy-king was a product of Edward’s new monarchy. Unfortunately the boy-king Richard II combined the lofty royal condescension of Edward III’s kingship with another less desirable Plantagenet character trait – he had that same strong stubborn streak the Plantagenet kings manifested most often in their overbearing irrational affections – blind loyalty to flawed friends and irrational hatred of supposed enemies.