The Devil is in the detail…….Gardiner versus Cranmer

Pope St Gregory I ( the Great b.540 d.604) reigned 590-604 responsible for creation of complete service books

“ Hail for evermore, Thou most Holy Flesh of Christ; sweet to me before and beyond all things beside. To me a sinner may the Body of our Lord Jesus Christ be the Way and the Life.”

These were the ritual words that were spoken inaudibly by the priest just before he took Holy Communion; that is, consumed the consecrated elements of bread and wine. Holy Communion composed the final ritual action of the Mass. The Mass was the medium in which the bread and wine were consecrated. But it was not its only function. The Mass was also a medium for commemorating the ritual sacrifice of Christ – as he instructed when he said: do this in memory of me.

For the reformers the questions were what precisely constituted these two elements? First, what happened to the bread and wine at consecration; secondly, if the cause of the gathering was the Eucharist what, if anything, was effected by this act of commemoration itself. In practice it was agreed that the ‘Mass’ was media for both sacred actions. The question was: what being transmitted and being received, both on earth and also in heaven? It was a straight question to which there was to be no straightforward answer.

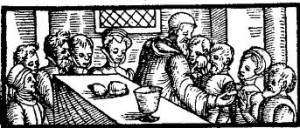

A depiction of the elevation in the Western Rite, which occurs after the words of institution – this is my body; this is my blood.

The words above were particular to the Mass according to the use of Salisbury. The rite of Salisbury is known usually as the Sarum rite. It was the principal usage of the English church until 1558 – save for the brief interlude between 1549 and 1553. It was the use of the Canterbury Convocation; the rite of its secular clergy; it was also the liturgical form used at court. It was also used in the Northern Convocation where there were other common uses notably those of Hereford, Chester and York. The regular clergy often had their own rite or would have used the Sarum rite with ritual emendations of their order.

Before the Council of Trent, all across Christian Europe, there were similar authorised local rites or uses for the Mass. These different rites incorporated many local practices. Forms of ritual practice or gestures of litugical greeting varied from region to region; sometimes from city to city. Some prayers and liturgical additions were often particular and differed between say Celtic, Anglo Saxon, Gallican or Mozarabic rites. Prominent in the Sarum rite were medieval poetic prayer-forms adapted for the use of the choir; they were called Tracts and Sequences and were inserted before and after the epistle and before the gospel. Their vivid language is luminous with the preoccupations of medieval religious faith. There were other significant variants in ritual actions – for example after the consecration the Anamnesis was said by priest with hands extended, visually replicating the position of the arms of the crucified Christ on the cross.

When Pius V promulgated the new Roman Missal in 1570 this local liturgical diversity characteristic of medieval Christianity was formally ended. Generally, from this point forward the Catholic rite was the single rite of the Roman missal. The Reformed rites remained more various; these were conducted in the vernacular; but nevertheless, they were usually prescribed to one uniform practice in each single political entity. The practical diversity of the old Mass was just another casualty of the religious revolutions that convulsed the Western Church in century or so after 1517 and which we know by the shorthand: Reformation; and Counter Reformation.

By 1500 the structure Mass by and large had been unchanged for five hundred years; its principal elements were recognisable from the missals a thousand years old. Prior to that, its broad form, if not its language, would have been similar for another three hundred years. The mass directly touched the stones of ancient Rome as well as being conducted in the language of her Empire. It both East and West it was the church’s oldest act of collective worship. It had bound Christians together in life and in death since early in the second century. Its pedigree stretched back yet further, through the practices of the early church to the very actions of Christ himself at the Last Supper as recorded in the Gospels. According to the Gospels it was the means by which the Christ made himself known to his followers after the Resurrection. Most compellingly, something of this same ceremony was practised even earlier than the time when the Gospels were composed. For this ceremony is discussed in the epistles, or letters, of St Paul to the Corinthians whose composition can be dated to the two decades after Christ’s crucifixion.

Missal is the name given to the manuscript books used to conduct this principal prayer of the church which, until the Reformation, had remained the church’s only continuous act of communal worship. The English word Mass had derived from the Latin, Missa – hence missal. The term Missa or Mass seems to come from the words spoken by the priest towards the end of the service when he or a deacon dismissed the congregation using the phrase: ‘ite missa est’. It is a corruption of the Imperial Roman command at the end of an audience, or the adjournment of a court or such : ‘(ite) dimissa est’ – (go forth) you are dismissed.

The term ‘Missa’ or ‘Mass’ dates from at least the fifth century. It certainly was in common use by the reign of Gregory I (the Great). Latin Mass dated from the third century – probably around the time of Constantine when Christianity became the Imperial religion. Before then the ‘Mass’ was a Greek rite……continued here…